Introduction

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is an acute-onset, post-infectious and immune-mediated disorder of the peripheral nervous system (PNS) including four basic disease patterns: acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP), acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN), acute motor-sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN), and Miller Fisher syndrome (MFS)1,2. Clinically, established GBS is subdivided into classical forms (exhibiting variable degree of areflexic tetraparesis [AIDP and axonal GBS (AMAN/AMSAN)], and localized forms (e.g., pharyngeal-cervical-brachial variant), whereas MFS presents with complete form (classic triad of ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, and areflexia) or incomplete forms (e.g., acute ataxic neuropathy)3. Half of the patients with AMAN or AMSAN are positive for anti-GM1 or anti-GD1a antibodies; in MFS, nearly all patients present anti-GQ1b antibodies; no specific antibodies have been detected in AIDP. Experimental autoimmune neuritis (EAN) is a widely accepted model of GBS4.

In this paper, we will focus on classic GBS forms. In clinical practice, the distinction between demyelinating and axonal subtypes is based on the results of conventional nerve conduction studies (NCS) performed in the established stage of disease1,2. However, it is worth noting that in very early GBS (≤ 4 days after onset), the histopathological hallmark is neither demyelinating nor axonal degeneration, given that at this early stage, the pathogenic lesion is inflammatory edema predominating in proximal nerve trunks5,6. This notion is also valid for P2-induced EAN7.

GBS patients presenting to the hospital in the first 4 days of the clinical course are mostly severe forms, whose conventional NCS usually demonstrate non-specific findings, which does not allow us to establish whether we are dealing with a demyelinating or an axonal disorder8–10. This fact is of utmost importance to understand the nosology of the syndrome. The aim of this work is to address the pathophysiological mechanisms that operate in very early GBS. We would like to advise the reader that our narrative and illustrations will only be those that we have used in our own papers on the mechanisms at work in the early stages of GBS11–13.

The current paper has been divided into nine sections, which will complementarily serve to compose a heterodox approach to the pathophysiology of very early GBS.

Early pathology in classic GBS

The first systematic autopsy study of GBS was carried out by Haymaker and Kernohan5, who collected the autopsy material of 50 fatal GBS cases during the Second World War, 32 of them having died from day 2 to 10 after symptom onset. According to the authors, “the observed pathological changes were more prominent where motor and sensory roots join to form spinal nerves. Edema of the more proximal part of the PNS was the only significant alteration the 1st days of illness. By the 5th day, clear-cut disintegration of myelin and swelling of axis cylinders were observed.”

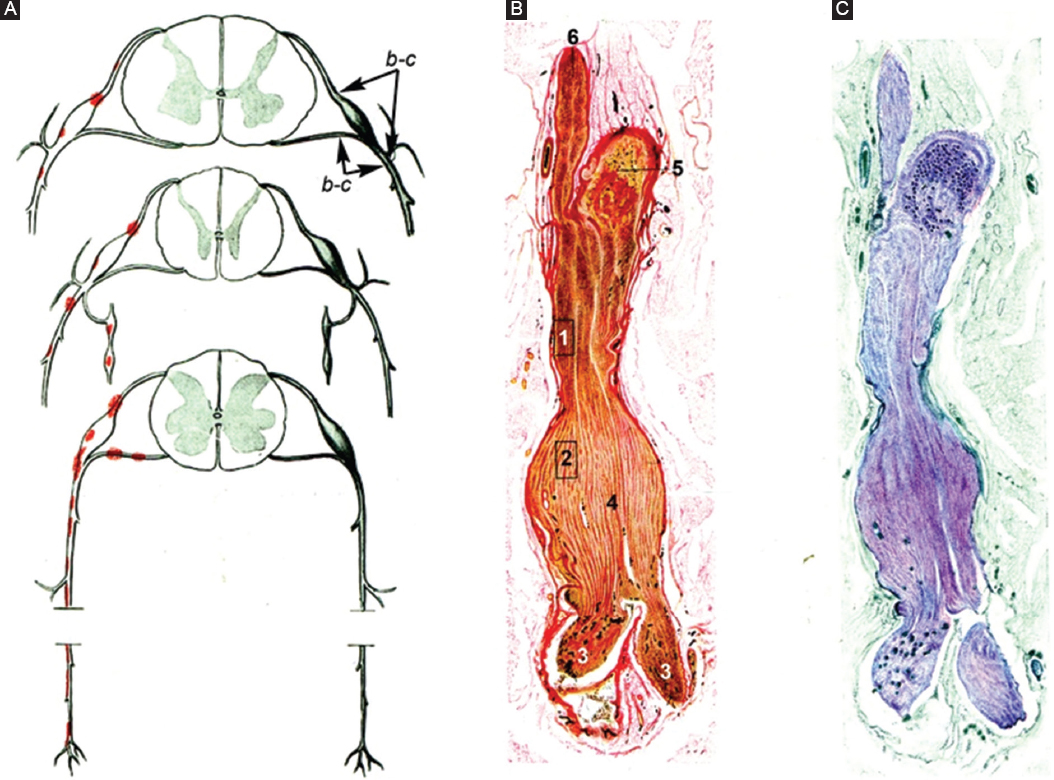

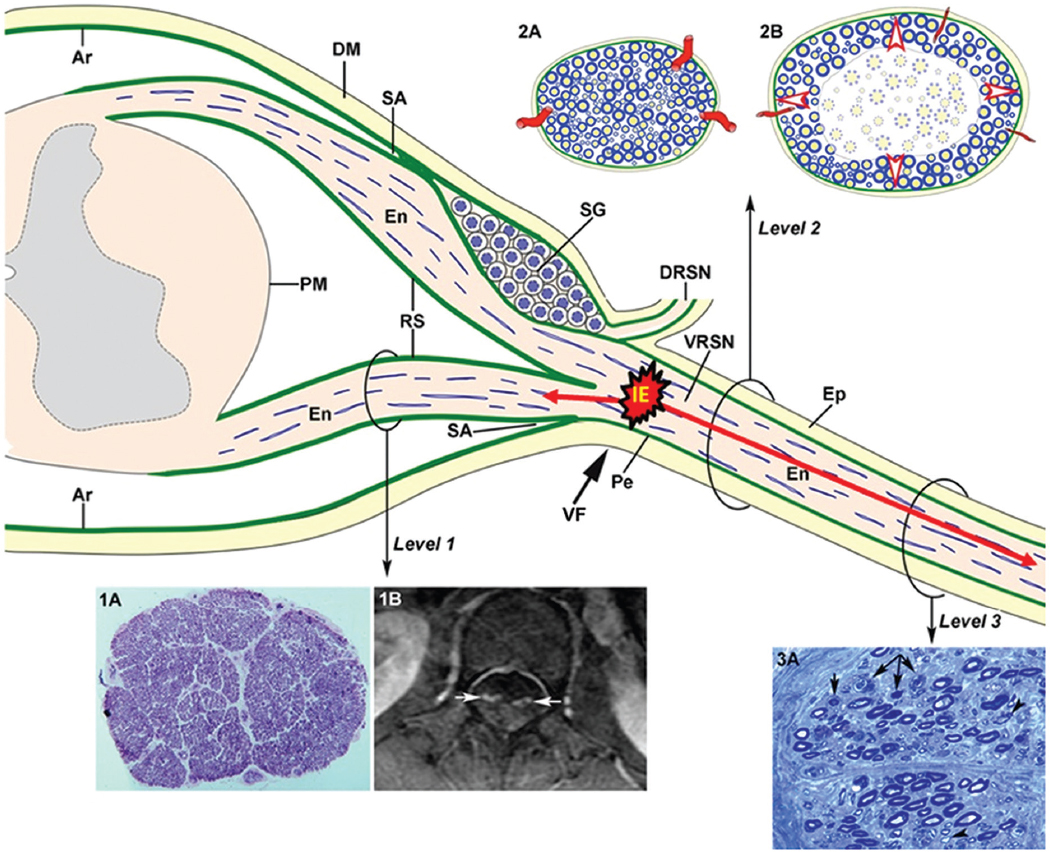

A few years later, Krücke6 performed a histopathological study of seven fatal GBS patients. Extensive histological sampling was taken from the PNS (Fig. 1A). Main lesions are reported, almost literally, as follows: “Nerve inflammatory edema was already observed in a patient died on the 1st day after onset […]. Endoneurial edema was accompanied by inflammatory cells; due the absence of pure serous exudation, as reported by Haymaker and Kernohan, edema is considered an integral part of the inflammatory process. In early stages of the syndrome, lesions were localized affecting predominantly proximal nerve trunks, particularly spinal nerves, where edema was sufficiently severe that it could be detected with the naked eye” (Fig. 1B and C). Florid demyelination was observed as of day 14. Intriguingly, we have observed similar findings in an early severe AIDP patient (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3)14.

Figure 1. Reproductions of Figs. 65-67 by Krücke6 with minimal modifications. A: diagram of GBS lesions at cervical (upper row), thoracic (middle row), and sacral (lower row) levels; note that they mainly rely on proximal nerves including ventral and dorsal spinal roots, spinal root ganglia, sympathetic ganglia, and ventral rami of spinal nerves (red dots). Lettering b-c indicates nerve segment illustrated in other figures reported by Krücke. B: longitudinal section of the nerve segment between ventral spinal root and spinal nerve from a GBS patient who died on day 18, original numbering being as follows: (1 and 2) areas illustrated by the author in other figures (specially his Fig. 68b showing abundant endoneurial inflammatory edema, which was designated as “mucoid exudate”); (3) rami of the spinal nerve (undoubtedly, ventral, and dorsal rami); (4) spindle-shaped swelling of the spinal nerve; (5) spinal root ganglion; and (6) ventral spinal root (Van Gieson, magnification not specified). C: the same longitudinal section showing a purplish discoloration of the spindle-shaped swelling of the spinal nerve (Cresyl violet, magnification not specified). GBS: Guillain-Barré syndrome.

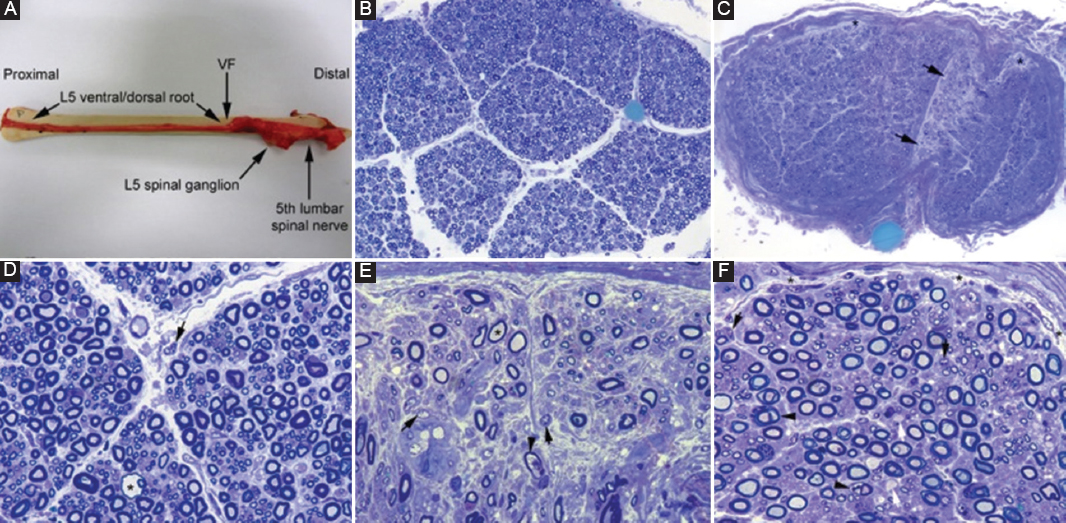

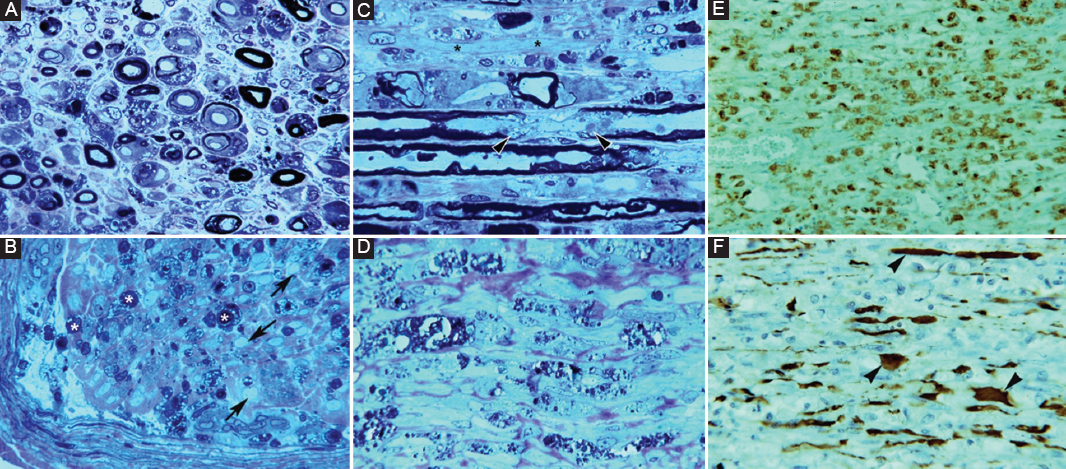

Figure 2. Pathological features from a severe acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy who died on 9th day after onset. A: after being dissected down, macroscopic appearance of the right L5 spinal root, L5 spinal ganglion and fifth lumbar spinal nerve. Whereas the pre-foraminal root shows normal morphology, as of the VF note visible nerve enlargement. B: semithin cross-section of L5 ventral root, taken 1 cm above its entrance to the VF, showing that the density of myelinated fibers is preserved (Toluidine blue; original magnification ×100 before reduction). C: semithin cross-section of the ventral ramus of the fifth lumbar nerve, taken at its emergence trough intervertebral foramen, showing widespread endoneurial edema, which is more conspicuous in septum adjacent areas (arrows) and sub-perineurial areas (asterisks); such edema results in a spacing out phenomenon giving an observer the false impression of reduced density of myelinated fibers (Toluidine blue; original magnification ×65 before reduction). D: high-power view of the L5 ventral root showing preservation of the density of myelinated fibers with occasional presence of mononuclear cells (arrow) and a fiber exhibiting myelin vacuolization (asterisk). E: high-power view of the sub-septum area arrowed in C. Note the presence of florid inflammatory edema with numerous mononuclear cells (arrows), fibers with inappropriately thin myelin sheaths (asterisk), and fibers exhibiting myelin vacuolation (arrowhead). Having in mind the spacing out phenomenon, note the false impression of reduced density of myelin fibers in comparison with L5 ventral root and sciatic nerve (Toluidine blue; original magnification ×630 before reduction). F: semithin section of sciatic nerve showing occasional demyelinated axons (arrows), fibers with vacuolar degeneration (arrowheads), and widespread but discreet endoneurial edema more marked in sub-perineurial areas (asterisks) with presence of mononuclear cells (arrows) (Toluidine blue; original magnification ×630 before reduction). VF: vertebral foramen. Adapted from Gallardo et al.14.

Figure 3. Electron micrograph of a subperineurial area of the fifth lumbar nerve (same the patient illustrated in Fig. 2) showing extensive edema on a ground substance of amorphous material, most likely proteoglycans, with sparse bundles of collagen fibrils. Note the presence of macrophages containing lipid droplets (asterisks) and numerous electron-lucent endocytic vesicles (arrows) and lysosomes. The edematous area is empty of myelinated fibers, the only one observed (MF) being separated about 20 mm from the inner perineurial layer; P indicates perineurium (Bar, 3 mm). Taken from Gallardo et al.14.

In a clinical-pathological paper encompassing 19 fatal GBS patients, five of whom having died within 9 days after onset (cases 1-5), Asbury et al.15 stated that “The common pathological denominator in all cases was an inflammatory demyelinative neuritis marked by focal, perivascular, and lymphocytic infiltrate, affecting at any level of the PNS […]. All levels of the PNS were vulnerable to attack, including the anterior and posterior roots, ganglia, proximal and distal nerve trunks and terminal twigs, cranial nerves, and sympathetic chains and ganglia […]. Varying amounts of Wallerian degeneration were also present, depending on the intensity and destructiveness of lesions.” Although this is the case in advanced stages of the disease16, it is worth noting that in two of their early cases (Nos 2 and 3) with pure motor signs, lesions predominantly affected the ventral roots, with more distant nerve trunks presenting minimal involvement. The authors suggested that, on the basis of the pathological features, GBS and EAN are a cell-mediated immunologic disorder, in which the PNS, particularly myelin, is attacked by specifically-sensitized lymphocytes, but stating “The question of edema is of some importance because it is not a prominent feature of the nerve and root lesions of EAN, and its alleged presence in idiopathic polyneuritis might be taken as evidence against accepting EAN as a valid model idiopathic polyneuritis. That no edema was observed in our series strengthens rather than weakens the homology between EAN and idiopathic polyneuritis. It may be that our histological criteria for accepting the presence of edema differ from those of others.” After this influential paper, the pathogenic role of inflammatory edema in very early GBS was overlooked for decades. However, the presence of endoneurial edema was demonstrated in later pathological studies17,18. Intriguingly, it has been established that edema may be a marker of disease in inflammatory neuropathies of recent onset19.

Chronology of initial lesions in P2-induced EAN

The chronology of initial lesions in EAN was masterfully reported by Izumo et al.7 in Lewis rats by inoculation with autoreactive T cells sensitized to residue of bovine P2 myelin protein. Almost literally, lesion evolution is reported as follows: “flaccid tail and weakness of the hind-limbs, started between 3.5 and 4 days post-inoculation (pi), which rapidly progressed to peak between days 7 and 9. On day 4 pi, the first pathological change was marked edema with or without cellular infiltrates in the sciatic nerve and lumbosacral nerve roots. Between days 7 and 9, while inflammatory edema declined, there appeared florid demyelination; independently of this, there were some nerve fibers showing distinct axonal degeneration.”

In a similar EAN model, at peak disease (day 6), there was minimal fiber changes: the mean number of demyelinated axons was 79/mm2 (0.7% of the total number), degenerating axons being 121/mm2 (1.0% of the total)20. Certainly, so low percentages of abnormal fibers do not account for semiology at peak disease.

In short, both EAN models demonstrate that inflammatory edema is pathogenic by itself at the onset of neurologic deficit.

Despite the similarities between GBS and EAN, it must be recognized that the symptomatic chronology of these disorders is different. In EAN, everything starts from the moment of antigen inoculation and appearance of the first signs of disease. Unlikely this, in GBS, it is the neuropathic symptomatology that heralds the onset of disease, but symptoms might be subtle and hardly noticeable to the patient.

Pathogenic role of endoneurial fluid pressure in P2-induced EAN

In EAN induced in Lewis rats by inoculation with autoreactive T-cell lines sensitized to residue 57-81 of P2 myelin protein, Powell et al.21 measured EFP in both sciatic nerves at 0, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 days pi. A significant increase in pressure was detected at 5 days pi, at which time EFP ranged from 4.0 to 6.1 cm H2O (baseline pressure < 2), the highest value being registered at 7 days pi when EFP ranged from 7.5 to 11.7. Worthy of note is the fact that endoneurial inflammatory and edema and an increase in extracellular space were the outstanding features in the first 7 days pi, when both demyelination and axonal degeneration appear. As wisely stated by Powell et al., “edema and increased EFP are believed to stretch the perineurium and constrict trans-perineurial microcirculation, compromising nerve blood flow and producing the potential for ischemic nerve injury.” The morphologic consequence of such perineurial constriction is the appearance of wedge-shaped or centrofascicular areas of endoneurial ischemia (Fig. 4)11–13,22–24.

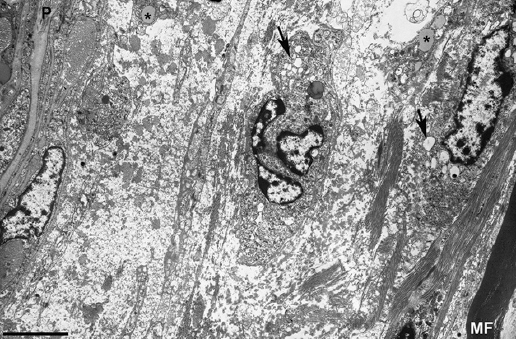

Figure 4. Ischemic nerve lesions in acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. A: semithin cross-section of the ventral ramus of the third lumbar nerve showing a wedge-shaped area (arrows) with marked loss of myelinated fibers (Toluidine blue; ×62 before reduction). B: semithin cross-section of the lumbosacral trunk with a centrofascicular area (arrows) also exhibiting marked loss of myelinated fibers (Toluidine blue; ×62 before reduction). Both in A and B note apparent widespread diminution of myelinated fibers. C: this high-power view of the central region of the lumbosacral trunk illustrates interstitial edema, severe reduction of large myelinated fibers, thinly myelinated small axons, preserved unmyelinated axons (arrowheads), and widespread endoneurial mononuclear inflammatory cells, some of them with perivascular distribution (arrows) (Toluidine blue; ×375 before reduction). D: this high-power view of the subperineurial region of the lumbosacral trunk shows numerous de-remyelinated fibers, edema, and mononuclear cells; such extensive demyelination accounts, to some degree, for the apparent widespread loss of myelinated fibers observed in image B (Toluidine blue; ×475 before reduction). Adapted from Berciano et al.25.

The blood-nerve barrier efficiency dictates initial GBS lesion topography, and the pathogenic role of the EPI-perineurium

The PNS possesses a blood-nerve barrier that restricts the passage of soluble mediators and cells from the bloodstream into endoneurium25. To this end, endoneurial capillaries are continuous presenting endothelial cells sealed with tight junctions and are fully surrounded by basement membrane and pericytes. Fenestrated capillaries, with pores of 80-100 nm of diameter, are only observed in spinal ganglia. In his classic experimental studies of vascular permeability in the PNS, using albumin labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate or Evans blue, Olsson26 almost literally described the following topographical differences: (i) “the ventral and dorsal spinal roots presented positive fluorescence, both within blood vessels and in interstitium of the fibers; this phenomenon extended to the junction with peripheral nerves (spinal nerves); (ii) extravascular fluorescence was very intense in the spinal ganglia; (iii) in the peripheral nerve trunks fluorescence was only visible in the vascular lumen; and (iv) intense fluorescence was observed both in the vessels and in the interstitium of the epi-perineurium.” Therefore, the vascular permeability is greatest in the spinal roots, spinal nerves, and spinal ganglia. Nerve terminals, just surrounded by presynaptic glia, lack the characteristic blood-nerve interface of the intermediate nerve trunks, which also implies greater permeability27, probably extending to pre-terminal branches.

Above-mentioned characteristics of endoneurial permeability are correlated with the distribution of early inflammatory edema in GBS, predominantly affecting proximal nerve trunks11–14. At this point, it is very important to remember the microscopic anatomy of the PNS (Fig. 5)28. Intrathecal spinal roots are surrounded by a lax and elastic arachnoid envelope that may accommodate early edema by increasing their cross sectional areas, but conceivably without significant changes of EFP. As of subarachnoid angle, proximal nerve trunks possess epi-perineurium that is relatively inelastic; here, inflammatory edema may increase EFP causing axonal damage (see above).

Figure 5. Diagram of spinal root and spinal nerve microscopic anatomy illustrating the topography of early GBS lesions and their consequences. As of subarachnoid angle (SA), the epineurium (Ep) is in continuity with the dura mater (DM). The endoneurium (En) persists from the peripheral nerves through the spinal roots to their junction with the spinal cord. At the SA, the greater portion of the perineurium (Pe) passes between the dura and the arachnoid (Ar), but a few layers appear to continue over the roots as the inner layer of the root sheath (RS). The arachnoid is reflected over the roots at the SA and becomes continuous with the external layers of the RS. At the junction with the spinal cord, the outer layers become continuous with the pia mater (PM). Immediately beyond the spinal ganglion (SG), at the SA, the ventral and dorsal nerve roots unite to form the spinal nerve, which emerges through the intervertebral foramen (VF; large black arrow) and divides into a dorsal ramus (DRSN) and a ventral ramus (VRSN). Therefore intrathecal nerve roots are covered by an elastic root sheath derived from the arachnoid, whereas spinal nerves possess epi-perineurium which is relatively inelastic. Proximal-to-distal early GBS inflammatory lesions are illustrated as follows: ventral lumbar root (level 1), spinal nerve (level 2), and sciatic nerve (level 3). At level 1, this semithin complete cross section of ventral L5 root shows preservation of the density myelinated fibers (1A), though inflammatory lesions, observable at higher augmentation (not shown), may account for increased surface area, and thickening and contrast enhancement of ventral roots on spinal magnetic resonance imaging (1B, white arrows). Both cartoons at level 2 illustrate the following features: (i) normal anatomy of spinal nerve, usually monofascicular with epi-perineurial covering (2A), which account for its sonographic appearance usually consisting of a hypoechoic oval structure surrounded by hyperechoic perineurial rim; and (ii) endoneurial inflammatory edema may cause a critical elevation in EFP that constricts transperineurial vessels by stretching the perineurium beyond the compliance limits (2B, arrowheads), which could result in areas of endoneurial ischemia, here centrofascicular. As illustrated herein (2A vs. 2B), despite low spinal nerve compliance, early inflammatory events in GBS may cause an increase of cross sectional area. Inflammatory edema (IE) may cause anterograde (centrifugally) axonal degeneration (longer red arrow) and retrograde axonal degeneration (short red arrow), which at earliest stages of the disease predominates in the distal segment of the anterior spinal root, as originally reported in AMAN30 and AMSAN31,32. At level 3, this cross semithin section of sciatic nerve from a fatal acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy patient shows several myelinated fibers exhibiting Wallerian-like degeneration (myelin collapse, small black arrows) secondary to more proximal inflammatory lesions; note the presence of remyelinated fibers (arrowheads) and lipid-laden macrophages. Without knowledge of proximal nerve pathology, such distal florid Wallerian-like lesions would make it very difficult to reach an accurate diagnosis. this diagram was inspired by Figs. 3–6 from Berthold et al.28. GBS: Guillain-Barré syndrome. Adapted from Berciano12–14.

Earliest histopathological changes of the spinal nerves also occur in AMAN/AMSAN

Originally recognized under the rubric of Chinese paralytic syndrome, McKhann et al.29 reported “36 patients from rural areas of northern China, aged from 15 months to 37 years (median, 7 years), admitted during a 2-week period in August 1990 with acute paralytic disease, whose electrophysiology showed compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitude reduction and normal motor conduction velocity […]. The disorder was considered a type of reversible distal motor terminal or anterior horn lesion.” It is worth noting that, despite being a “pure” motor disorder, many patients had neuropathic pain, sometimes very prominent and accompanied by meningeal signs.

Two years later, McKhann et al.30 reported the results of 10 autopsy studies showing non-inflammatory Wallerian-like degeneration of motor fibers in 5, demyelination in 3, and absence of lesions in 2. The acronym AMAN was applied to cases showing selective degeneration of motor fibers; in this regard, the authors wrote that “the major pathological finding was Wallerian-like degeneration of the ventral roots and, usually to a lesser degree, of motor fibers within the peripheral nerves; the proportion of degenerating radicular fibers increased distally toward the ventral root exit from the dura where 80% of fibers were degenerating,” namely, the greatest pathology was found in spinal nerves. One could wonder why main changes are located within spinal nerves in a primary motor axonopathy. We will go into this issue in the next two paragraphs.

Afterward, the histopathological features of the Chinese paralytic syndrome were reassessed by Griffin et al.31,32 in two series encompassing 16 patients, whose autopsies were performed between 3 and 9 days after onset in 11 of them. Focusing on their early cases, two were classified as AMAN, three as AMSAN, three as AIDP, and the remaining three as minimal pathology. As stated by the authors, “The pathological picture suggested that the most initial lesions were in spinal roots, rather than in the peripheral nerves […]. Some degenerating fibers could be identified within 100-200 mm of the ventral root exit zone […]. The process of Wallerian-like degeneration was at more advanced stage in the roots than in the nerves. Because Wallerian degeneration proceeds centrifugally from the site of axonal interruption down affected fibers, the picture is consistent with interruption of most degenerating fibers at the level of spinal roots, rather than the peripheral nerves.” AMSAN histopathological features were considered similar to those reported by Feasby et al.33 for the acute axonal form of GBS, but wisely adding that “Strictly speaking, these cases are neither non-demyelinating nor non-inflammatory, but rather predominantly axonal and minimally inflammatory.”

In short, the original pathological studies of early AMAN and AMSAN demonstrate that the brunt of changes, as in AIDP, is located at the ventral root exit from the dura, that is where anterior and posterior roots unit to form the spinal nerve and where dura mater is in continuity with epineurium. Although endoneurial edema is not specifically mentioned, this could go unnoticed. Based on previous autopsy studies (see above) and further pathological and imaging studies (see below), there is a rational basis to propose that initial inflammatory edema mainly involves spinal nerves where, when critical enough, it has the following effects (Fig. 5): (i) EFP increase; (ii) ischemic conduction block to be detected exploring late electrophysiological responses (see below); and (iii) axonal damage manifested as Wallerian-like degeneration, both centrifugally in more distant nerve trunks, and centripetally predominating in distal parts of intrathecal spinal roots as masterfully described by the Griffin et al.31,32.

Electrophysiological studies in very early classic GBS

In very early GBS, NCS have shown that dichotomous classification of GBS, as axonal or demyelinating, is only possible in 20% of cases, serial electrophysiological explorations being necessary to better categorize GBS subtyping8–10,34. The most frequent electrophysiological findings were abnormal late responses (absence of H reflex and F wave abnormalities) and reduced distal CMAP amplitudes; furthermore, there may be nerve inexcitability at first electrophysiological evaluation34–37. In interpreting these very early electrophysiological alterations, it is important to remember that pathological studies have shown that the only underlying alteration is inflammatory edema, when neither demyelination nor axonal degeneration has entered into the scene. In nerve trunks possessing epi-perineurium, such edema may induce endoneurial ischemia (see above), which experimentally can lead to nerve conduction failure within minutes38.

There are no histological studies of pre-terminal motor segments to establish the possible presence of areas of endoneurial ischemia in GBS, as has been depicted in proximal nerve trunks (Fig. 4). We do, however, have an elegant electrophysiological study performed in a patient with severe AIDP on the 5th day of evolution, on whom Brown et al.39 recorded changes in extensor digitorum brevis (EDB) maximum potentials in response to supramaximal stimulation of the deep (anterior) tibial nerve 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 mm to the innervation zone. Advancing the site of stimulation to within 20 mm of the EDB motor point, there were three- and nine-fold increases in the respective M responses (around 0.95 mV; normal ≥ 2 mV), the most attenuated M response occurring after stimulation from 100 mm (around 0.05 mV; see figure 1 in Brown et al.39). Such electrophysiological features indicate that presumably conduction block is located not at the motor terminal of the tibial nerve, but more proximally somewhere in the pre-terminal motor segment, already endowed with epi-perineurium.

After the above-mentioned papers by Asbury et al.15 and McKhann et al.29,30, AMAN has been widely regarded as a model of motor neuropathy due to involvement of terminal nerve segments. The question arises as to whether this is the case. We will try to give an accurate answer. But before that, it seems pertinent to briefly remind readers of the microscopical anatomy of the PNS28,40, complementary to the one already described in figure 5. Starting at the subarachnoid angle, the ventral and dorsal roots merge to form the spinal nerves, mono or bi-fascicular structures in which the dura mater becomes epineurium and the subdural arachnoid becomes perineurium28. The peripheral nerve trunks are multifascicular; their tracts possess perineurium, and all are surrounded by epineurium. These nerve trunks present low compliance, but provide mechanical protection to nerve fibers. When they reach the muscle, texture of intramuscular nerve branches changes: they comprise myelinated fibers and unmyelinated fibers enclosed by Schwann cells with their basal membranes; more peripherally the perineurium is reduced to a layer of three or four flattened cells (perineurial epithelium) containing external and internal basement membrane, although this is discontinuous. More externally the epineurium is reduced to two or three layers of cells lacking basement membrane, joined by longitudinal collagen bundles. Approaching to neuromuscular junction, myelinated fibers lose their myelin sheath, adopting the morphology of the node of Ranvier; this external axon, covered only by Schwann cells with their basement membrane (synaptic glia), enters the synaptic cleft, where the Schwann cell membrane fuses with basement membrane of the sarcolemma. A thin perineurial epithelium accompanies the terminal axon until 1-1.5 mm from its contact with the neuromuscular junction; therefore, the terminal segment of the axon is only separated from the surrounding connective tissue by perisynaptic glia (for more details, see the diagram in figure 6 of the article by Saito and Zacks27).

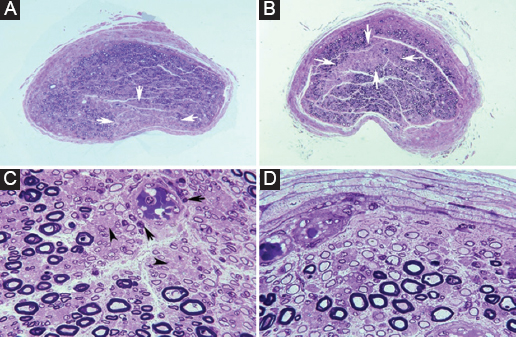

Figure 6. Pathology in fulminant Guillain-Barré syndrome with very early universal nerve inexcitability (see text); autopsy was performed on day 18. A: semithin cross section of L5 ventral root showing massive demyelination and numerous lipid-laden macrophages and endoneurial edema (Toluidine blue; ×630 before reduction). B: semithin cross section of femoral nerve illustrating marked axonal degeneration (asterisks). Note the presence of denuded axons (arrows) and endoneurial and subperineurial inflammatory edema (Toluidine blue, ×630 before reduction). C: longitudinal semithin section of L5 ventral illustrating paranodal (arrowheads), denuded axons (asterisks) and lipid laden macrophages (Toluidine blue ×630 before reduction). D: longitudinal semithin section of femoral nerve showing that normal texture has been substituted by digestion chambers intermingled with collagen bundles, which are indicative of extensive Wallerian-like degeneration (Toluidine ×630 before reduction). E: paraffin-embedded longitudinal section of ventral spinal root showing diffuse macrophage infiltration (CD68 ×120 before reduction). F: paraffin-embedded longitudinal section of ventral spinal root showing that neurofilaments are relatively preserved, although some of them exhibit dystrophic features (arrowheads) probably due to loss of their myelin envelop (Neurofilament ×240 before reduction). Adapted from Berciano et al.35.

The notion of terminal branch involvement in early GBS has had deep roots in the literature since it was first proposed by Asbury et al.15. It is implicitly associated with that of a special vulnerability of the terminal segment of axons or in proper terms the presynaptic axon and its peri-synaptic glia. No histopathological studies of this nerve segment have been conducted in very early classic GBS, although two papers do address the pathology of the distant branches, which merits a brief analysis.

Hall et al.41 studied the case of a 55-year-old patient with fulminant GBS requiring mechanical ventilation. NCS on the 4th day revealed great reduction in distal CMAP amplitudes (0.12 mV in the median nerve), prolonged distal motor latencies (DML; 10 ms), and minimally reduction of motor conduction velocity (MCV; 46 m/s). The patient slowly improved and was able to walk unaided at 252 days of onset. On day 16, a biopsy study of a distal branch of the left musculocutaneous nerve showed marked sub-perineurial edema, macrophage infiltration, and demyelinated axons. As the material corresponds not to the terminal motor axon but to a macroscopically distant branch (pre-terminal) of the musculocutaneous nerve, the pathological findings fully coincide with what my research group described in AIDP35, despite the lack of secondary axonal degeneration (Fig. 6). The early, sharp reduction in CMAP amplitude is most probably explained by endoneurial ischemia of the pre-terminal segments of the studied nerve.

Ho et al.42 described a case of AMAN in a 64-year-old patient with history of diarrhea, who, in consecutive examinations, presented areflexia and ascending weakness that prevented her from walking. Anti-GM1 IgG antibodies were detected in serum. The patient recovered quickly after treatment with plasmapheresis. NCS on day 7 showed loss of excitability of the peroneal nerve. In median and ulnar nerves, there was attenuation of distal CMAPs with preservation of DML and MCV. On day 16, a motor-point biopsy of the gastrocnemius muscle revealed intramuscular nerves with myelinated fibers presenting myelin breakdown, normal unmyelinated fibers, and small numbers of preserved myelinated fibers. Immunostaining with cholinesterase and stained for axons with antibodies against protein gene product 9.5 revealed neuromuscular junction denervation. The authors concluded that in AMAN, paralysis “may reflect degeneration in motor nerve terminals and intramuscular axons.” Another interpretation is possible: the findings described here may simply be the consequence of an inflammatory process affecting pre-terminal nerve fibers.

An argument against the pathogenic role of motor nerve terminal damage is the absence of abnormal jitter in response to axonal stimulation, both in AIDP and AMAN43.

Special electrophysiological studies demonstrating proximal pathology in early GBS

In recent times, several advances have added accuracy for GBS diagnosis. It is well-known that histopathological changes in any early GBS subtype often predominate in proximal nerve trunks11, their detection having been improved by means of electrophysiological measurement at Erb’s point44, electric motor root conduction time45, electric lumbar root stimulation46, and triple stimulation technique (TST)47.

Intriguingly in 6 AMAN patients, examined between days 1 and 6 (median, 4.5) and whose conventional NCS did not fulfill the electrophysiological criteria of GBS, TST demonstrated that all six patients had proximal conduction block situated between root emergences, namely, ventral rami of spinal nerves and Erb’s point47. Therefore, these electrophysiological features correlates extremely well with pathological and US studies showing that spinal nerves are a hotspot in any early GBS subtype (see below).

It is worth noting that pathological studies in axonal GBS mouse models sensitized with ganglioside GM1 have shown that complement is deposited in the Ranvier node in the early stage, disrupting Na channel aggregation48,49. This results in conduction block (eventually reversible conduction failure) by elevation Na+ channel opening threshold. Such abnormality is likely to occur at nerve roots and nerve terminal where blood-nerve barrier is vulnerable.

Imaging studies demonstrating proximal pathology in early GBS

Post-contrast T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging studies of the spinal cord and intrathecal spinal roots display radicular contrast enhancement in the vast majority of GBS that is already visible from early stages of the syndrome50,51. Such enhancement may be circumscribed to the ventral roots in cases of pure motor GBS52,53, which correlates well with histopathological studies showing selective involvement of these roots54. Spinal nerve hyper-intensity has been well illustrated with short-tau inversion recovery sequences56,56.

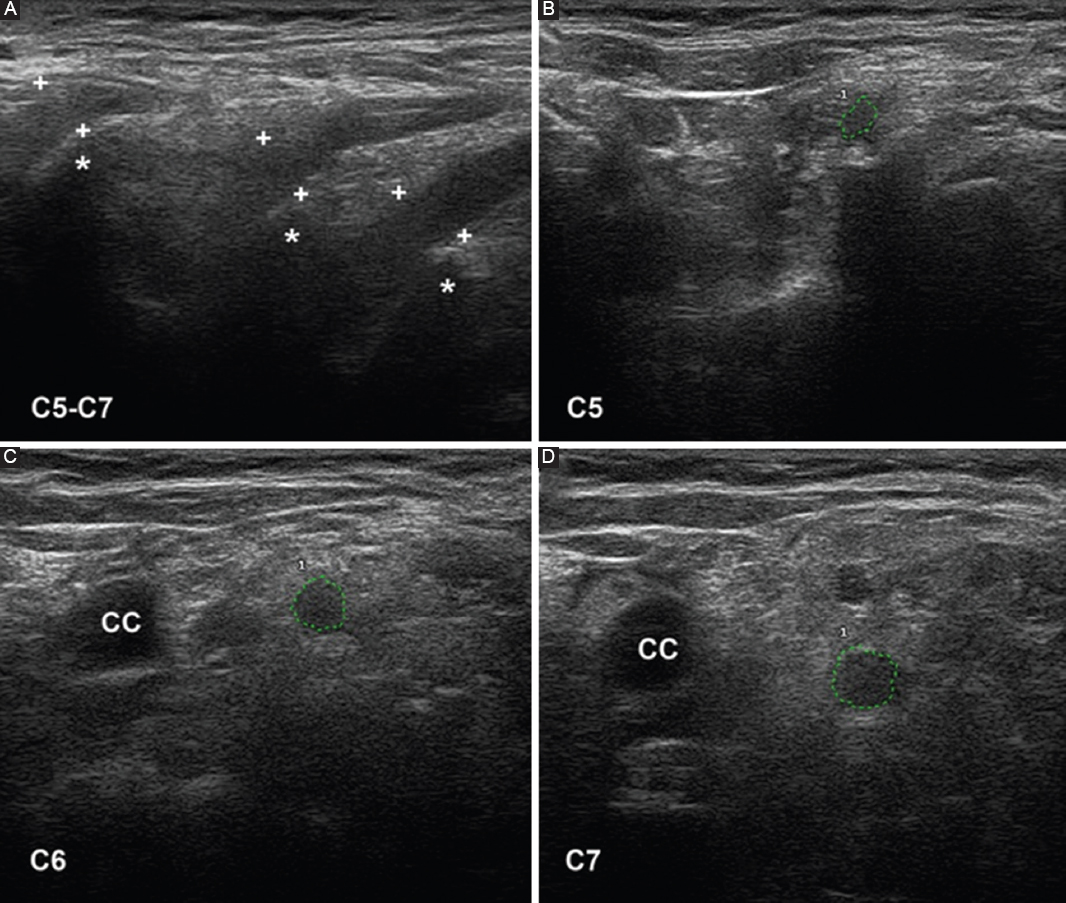

Ultrasonography is a useful diagnostic technique for studying PNS pathology57. With colleagues I have conducted an ultrasonography study in six consecutive patients with early and severe GBS, four categorized as AIDP and two as AMSAN14. The outstanding sonographic alterations were located in ventral rami of C5-C7 nerves, and consisted of significant increase of cross-sectional areas, blurring of the epineurial hyperechoic rim or both (Fig. 7). In a fatal case of AIDP, there was an excellent correlation between sonographic and histopathological studies (Figs. 1–4 in Gallardo et al.14). Furthermore, a striking difference in the degree of pathology was observed between lumbar roots, lumbar spinal ganglia, ventral rami of lumbar nerves, and more distant nerve trunks (Fig. 2). These findings again confirm that inflammatory edema of the spinal nerves is a hotspot in early stages of GBS11,12 (Figs. 2 and 3). Our ultrasound findings in the cervical nerves have been confirmed in other studies58–61, though there were discrepancies regarding the frequency of alterations in more distant nerve trunks. Considering that sonography results depend on the skill of the clinician performing the study, there is a great need for new prospective studies with international consensus62.

Figure 7. Ultrasound study of the ventral rami of nerves C5-C7, obtained on the 5th day of progression in a patient with fulminant acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (same patient as in figures 2 and 3). A: sagittal images showing disappearance of the epineurial hyperechoic rims (crosses indicate calipers; asterisks indicate the transverse processes). B-D: short-axis ultrasound of the three cervical nerves, whose perimeters are marked with green dotted lines; their cross-sectional areas are abnormally large. Note the disappearance of the epineurial rims. CC: common carotid artery. Taken from Gallardo et al.14.

Serum neurofilament light chain (NfL) and peripherin as biomarkers of axonal damage: would they be expected to be increased at the very early GBS stage?

NfL is a neuronal cytoplasmic protein highly expressed in large caliber myelinated axons. Its levels increase in cerebrospinal fluid and blood proportionally to the degree of axonal damage in a variety of neurological disorders. New immunoassays able to detect biomarkers at ultralow levels have allowed for the measurement of NfL in blood, thus making it possible to easily and repeatedly measure NfL for monitoring diseases’ courses63.

There have been four reported series of very early classic GBS, either demyelinating or axonal, describing serum levels of NfL or peripherin64–67. Intriguingly, both biomarker levels were increased in most patients with no significant differences between demyelinating and axonal subtypes, though higher levels correlate with poor outcome. To explain the mechanism of axonal damage in AIDP, it has been argued that66 “Recent ideas of GBS being a spectrum of nodo-paranodopathy with varying degrees of paranodal and axonal damage determining the electrophysiological phenotype may be supported by these data. Although almost all GBS cases in the UK are demyelinating, the data here suggest peripherin consistently raises indicating axonal damage in most cases.” This author argued that not being AIDP a form of nodo-paranodopathy, there should be other mechanisms to explain such axonal damage68.

The above-mentioned biomarker studies demonstrating axonal damage in any early GBS subtype are an exciting area of study, which merits special reflection.

In classical P2-induced EAN model, using conventional immunogen doses (25 mg SP26), inflammatory edema and demyelination were the predominant histological features in lumbosacral roots and sciatic nerves69. Quadrupling the immunogen doses, spinal roots continued exhibiting inflammatory demyelination whereas axonal degeneration and accentuated inflammatory edema were the outstanding lesions in sciatic nerves. The authors interpreted that axonal degeneration is caused by a more florid inflammation of distant nerves in comparison with spinal roots, macrophages appearing to be the major effectors in axonal destruction. This proposal was not confirmed in our detailed clinical-pathological study of a fulminant GBS patient showing universal nerve inexcitablity on days 3, 10, and 17 after onset35. Postmortem examination (day 18) showed pure demyelination in nerve roots and mainly axonal degeneration in more distant nerve trunks (Fig. 6). This discordant lesion topography had been associated with a bystander effect, with more intense inflammatory reaction at higher immunogen doses and in extradural nerve trunks. We then argued that this mechanism did not seem to apply in our material, as macrophage infiltration was comparable in the roots and more distant nerve trunks. Having in mind the seminal papers reporting the relevance of early spinal nerve pathology11,12, we wondered whether the appearance of epi-perineurium at the subarachnoid angle might play a pathogenic role in early stages of GBS (Figs. 2 and 5). The positive answer to this question was given in three clinical-pathological studies13,23,24 (Fig. 2). Furthermore, as in EAN22, we have reported areas of endoneurial ischemia in nerve trunks possessing epi-perineurium (Fig. 4). Therefore, abnormal levels of NfL or peripherin in any early GBS subtype, pointing to axonal damage, is most probably accounted for by endoneurial ischemia associated with inflammatory edema of proximal nerve trunks possessing epi-perineurium. As stated by Powell and Myers70, “whereas brain edema is universally understood as medical emergency, the destructive impact of endoneurial edema is less well appreciated; measures to inhibit edema and to ameliorate its effects have potential importance in protecting nerve fibers from ischemic injury.” Namely, there may be a therapeutic window for the use of intravenous glucocorticoids in early, severe GBS; furthermore on the basis of clinical and experimental data previously analyzed, I think that it would be worth testing to inhibit endoneurial edema as soon as possible, probably combining corticosteroids and plasma exchange or intravenous immunoglobulin regimen9,71.

As aforementioned, in AMAN, the major pathological finding is extensive Wallerian-like degeneration of the ventral roots and, usually to a lesser degree, of motor fibers within the peripheral nerves. AMAN is considered a prototypic example of acute nodo-paranodopathy, whose immunopathologic cascade begins with anti-ganglioside antibody (IgG1 and IgG3 subclass) deposition at the node of Ranvier, activation of complement, and formation of membrane attack complex (MAC) that induce Nav loss, paranodal myelin detachment, and finally nodal lengthening. With advance of the immune attack, Ca2+ penetrates into the axon trough the pores formed by MAC activating proteases, as calpain that causes damage of neurofilament and ultimately axonal degeneration2,36,48,72,73. Therefore, axonal degeneration in early AMAN may be associated with ischemic damage of proximal nerve trunks and presumably pre-terminal nerve segments, nodo-paranodopathy, or both mechanisms.

Conclusion

Inflammatory edema is the outstanding pathological feature for any subtype of very early classic GBS, which predominates in proximal nerve trunks, particularly in spinal nerves. In nerve trunks possessing epi- perineurium, which is relatively inelastic and of low compliance, such edema can critically increase EFP causing pathogenic nerve ischemia, manifested as rapid nerve conduction failure, ascending paralysis and abnormal serum levels of axonal damage biomarkers. Knowledge of microscopic anatomy of the PNS and initial clinical-pathological events, although it may seem a heterodox approach, is fundamental to understanding the nosology of established GBS.

Acknowledgments

I thank my colleagues of the Service of Neurology (HUMV, Santander), Drs. Antonio Garcia and Pedro Orizaola (Service of Clinical Neurophysiology), Dr. Elena Gallardo (Service of Radiology), Drs. Nuria Terán-Villagrá and Javier Figols (†) (Service of Pathology), and Professors Miguel Lafarga and Maria T. Berciano (Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, UC) for their help in clinical, electrophysiological, imaging and pathological studies.

Funding

This work has not received any official grant, scholarship, or support from research programs aimed at the preparation of its content.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest related to the content of this work.

Ethical considerations

Protection of humans and animals. The author declares that no experiments involving humans or animals were conducted for this research.

Confidentiality, informed consent, and ethical approval. The study does not involve patient personal data nor requires ethical approval. The SAGER guidelines do not apply.

Declaration on the use of artificial intelligence. The author declares that no generative artificial intelligence was used in the writing of this manuscript.