INTRODUCTION

It has been more than a century since the Spanish scientist Santiago Ramón y Cajal demonstrated for the 1st time that neurons or “the mysterious butterflies of the soul” as he used to call them, were independent cells1, nevertheless, it is through synapses or communication with other neurons that they manage to work together in an organized manner. We could extend such approach to the initiatives that have been conceived internationally for the study of the human brain which, albeit defined by independent criteria and methods, among its virtues stands out the collaborative effort of scientists, physicians, engineers, and researchers in the field of neuroscience.

Beyond describing in detail international initiatives inspired by the functioning of the human brain, we will provide a few hints on the challenges that have been achieved and the most relevant technological capabilities, in order to understand how they differ from other projects and the strategic vision of Europe within the framework of neurotechnologies. In this sense, the projects with greater impetus in the study of the brain both for the objectives set and for the economic, physical, and human resources began in Europe in 2013 with the Human Brain Project (HBP) –as an Emblematic Research Initiative of Future and Emerging Technologies, FET Flagship2– and shortly thereafter, NIH BRAIN Initiative3, in the United States. The HBP formally ended in September 2023 leaving as a legacy to EBRAINS (https://www.ebrains.eu), a digital research infrastructure in neuroscience, paving the way for the next generation of specialised tools for the simulation and modelling of the human brain –and other animals– at the molecular, mesoscale and macroscale4. EBRAINS offers technologies and services in data, brain atlases, modelling, simulation, validation, health research platforms, among others.

INTERNATIONAL INITIATIVES FOR THE STUDY OF THE HUMAN BRAIN

Similar to EBRAINS, the NIH BRAIN Initiative has evolved on a multidisciplinary collaboration scheme, achieving a deeper understanding of neural circuits in human and animal models. It currently focusses on three major projects5,6: a complete atlas of the types of cells of the human brain, a map of brain micro-connectivity and advanced tools for better definition and modelling of neural circuits. But, above all, the proposals –perhaps ahead of his time– that deal with the ethical aspects were visionary, better known as NeuroRights7, defined by the scientist Rafael Yuste.

In the United States, through the The NeuroRights Foundation8, NeuroRights form a corpus of individual freedoms aimed at protecting personal identity and mental privacy from possible monitoring, manipulations, or controls by other individuals and public or private organisations. So far there are five proposed neurorights that could be included to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the near future, simplified below9: the right to identity or control both physical and mental integrity, the right to freedom of thought and free will, the right to mental privacy, the right to fair access to mental augmentation or an equitable distribution of capabilities in the population and, finally, the right to protection against algorithmic bias. The growth of neurotechnologies has crossed the frontier of the clinical context to enter the realm of the consumer behaviour that, together with the use of artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms and increasingly sophisticated technologies, raises varied concerns about defining their limitations. In this sense, the inclusion of neurorights worldwide should be addressed as a priority, rather than a set of recommendations or moral principles.

On the other hand, other not negligible projects started before HBP and NIH BRAIN Initiative, were the Allen Brain Atlas, USA (2003)10, the European consortium Genes to Cognition (G2C) Project (2009)11,12, and the Human Connectome Project (2010)13. The first of them currently offers a varied and comprehensive range of mouse, human and other primate brain atlases. It started with the development and publication of the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas, a map of the gene expression of the entire genome of an adult mouse, with inspires the creation of the first gene expression atlas in the mouse’s spinal cord and the connectomic map or Allen Mouse Brain Connectivity Atlas10. Subsequently, the atlas of the human brain or Allen Human Brain Atlas was published which combines gene expression with anatomical structure and the BrainSpan Atlas of the Developing Human Brain to analyse the role of genetic organisation during gestation and other neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism. Likewise, it is noticeable how the institute has expanded its activities in the US thanks to the building of its own centres, the investment of human resources and technological equipment; favouring the expansion of new specialties. Some of them focus on the cell scale (predictive models, collection of genetically edited stem cells), neuroscientific (addition of different types of nerve cells to their database, 3D construction of their shapes and anatomies, neurodegenerative diseases, neural dynamics in cognitive processes), immunology (applied to oncology, autoimmune diseases), among others.

The G2C program was a consortium coordinated by the United Kingdom in 2009 that promotes the development and publication of a curated and experimentally validated database linking genes, proteins, and anatomy of the nervous system from studies in the field of electrophysiology and synaptic signalling11,12. It has managed to diversify into six areas: Behavioural (offering a collection of proteins related to cognitive processes, associated neurological diseases and genetic mutations in mice and humans); Electrophysiology (study of postsynaptic proteins in mouse brain slides, experiments with electrophysiological methods to measure neuronal electrical activity); Gene selection (use of techniques to study the functions of synaptic proteins in mutant mice); Human genetics (genes, synaptic plasticity, mutations); Computer science (in addition to its database, ML-based systems for gene selection); and Synaptic proteome (neuroproteomics, offering a molecular catalogue in healthy and diseased subjects). This system has evolved into a new proteomic database called Synaptic Proteome Database14, part of the HBP, so far, the most complete integrating 58 published datasets and more than 8,000 proteins. In a recent demonstration of the research team, following the identification of presynaptic, postsynaptic and synaptosome human genes, they created a genetic map15, in which the genes involved in any type of neurological disease, such as Alzheimer’s, can be selected.

Another project started in the same year was the Human Connectome Project (HCP) promoted by NIH with the aim of “construct a map of the complete structural and functional neural connections in vivo within and across individuals.” 13,16. They developed a database and analytical methods for sharing neuroimaging data in healthy adults, providing images of high sensitivity, specificity, and resolution, free of charge to the research community. They took the lead at the time to share an extensive map of structural and functional connectivity of 1,200 young adults to analyse the relationship between behaviour and lifestyle16. Other relevant aspects have been the addition of neuroimaging genetic analysis at the individual level and psychological evaluations. As for the first, they collected genetic material from blood and saliva samples from relatives, more than 1,142 samples –including dizygotic and monozygotic twins– which were later combined with neuroimaging assessments. On psychological tests, a wide range of behavioural measures are included from mood changes, anxiety, substance abuse, cognitive functions, self-reports, sensory processes, to hormonal measures and sleep quality16.

Brain/MINDS or Brain Mapping by Integrated Neurotechnologies for Disease Studies17 is the Japanese project born in 2014 that, unlike other international projects, was initially inspired by the development of the brain model of the marmoset or Callithrix jacchus, expanding its horizons to translational research, neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders. At present, they excel in four divisions: Creation of a structural and functional map of the monkey brain in its different temporal and spatial scales; development of neurotechnologies for brain mapping; human brain mapping together with clinical research; and, finally, the application of advanced neuroscientific methods and tools –optical and electron microscopy, neuroimaging equipment, etc.18–. Furthermore, the choice of the marmoset monkey brain as an experimental reference model in non-human primates favoured feasibility in their studies based on its parallelism with the human brain, in contrast to other international projects that experiment largely with rodents. Among its successes are also models of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in the marmoset monkey, including genome editing in these species, developing lines of research and therapies with high possibilities of being transferred to humans.

The Canadian CBRAIN project began in 2015 with a 9-year lifespan, with one of its most representative technologies being the Canadian Open Neuroscience Platform (CONP) for the processing, analysis, and visualisation of data in neuroscience. It is conceived as a web access tool for both the Canadian scientific community and international collaborators, in which data of any modality can be processed (from neuroimaging, genetic, health, etc.), consult guidelines for the publication of manuscripts and, ultimately, strengthen the multidisciplinary scientific networks that comprise its committees19. During 2023 the platform reached 90 digital tools and 70 federated databases, relying on supercomputing or HPC platforms. Its collaboration initiatives with international projects such as INCF, TVB, NeuroData Without Borders, among others.

Meanwhile, China and South Korea, which started their projects shortly thereafter, had a keen eye towards the development of tools aimed at neurological diseases with an emphasis on big data and AI. Although the planning of the China Brain Project (CBP) began in 2016, it was formally launched in 2021 on a triadic approach, whose central axis seeks to understand the neural basis of cognitive functions, develop advanced tools that facilitate the early diagnosis of neurological diseases and, finally, the creation of intelligent technologies inspired by the brain20. To advance in the central axis, they start from animal experimentation for the construction of a brain atlas with genetic and proteomic data, including the study of child neurodevelopment. It first results appeared in 2016, the Human Brainnectome Atlas 21 thanks to the application of neuroimaging techniques and the integration of multimodal data, identifying and delimiting with high precision brain sub-regions that other tools have not been able to reach. Other objectives of the CBP are technologies inspired by the brain, being AI its greatest ally for the creation of chips and computational cognitive models. However, in an interview with the neuroscientist Mu-Ming Poo20,22, the concern of CBP in China focuses on the diagnosis and treatment of neurological diseases of its large population, as well as those related to aging, so they are currently working on the development of technologies that can be transferred to the clinical context. In this sense, they collaborate with hospitals in Shanghai, which maintain a large amount of data that they can analyse and standardise to accelerate their R&D approaches.

In the Southeast Asia, the Centre for Brain Research (CBR) within the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) in Bengaluru, India, is involved in four Flagships projects focused on aging and related diseases: CBR-SANSCOG, CBR-TLSA, GenomeIndia and YLOPD Study23. The first is a longitudinal cohort study to assess cognitive changes in 10,000 participants over 45 years old from a rural community in the state of Karnataka. Over 10 years, they plan to perform clinical, neurocognitive and biochemical analyses23, generating a unique database regarding their population, including genetic and environmental factors, with the aim to identify further risk factors that Western studies have not been able to reach. The second Flagship CBR-TLSA is another longitudinal cohort study with similar objectives –to find risk and protective factors related to cognitive changes with aging–, evaluating about 1,000 participants from Bangalore23. As for the third Flagship or GenomeIndia, funded by the Department of Biotechnology, involved 20 national institutions to determine genetic variations by sequencing the genomes of 10,000 people from different regions in India. The project was officially completed in February 2024, generating a useful database to create personalised therapies and drugs24. Finally, the Young and Late-onset Parkinson’s Disease (YLOPD), is a longitudinal cohort study aimed at investigating Parkinson’s Disease in 1,000 patients from the earliest symptoms. In addition, they are inspired by mouse models23 in order to deepen their understanding of the molecular dynamics associated with motor and non-motor symptoms through behavioural experiments and histopathological test, among others.

On the other hand, the Korea Brain Initiative (2016), with a 10-year time horizon, dives into the development of neurotechnologies and the strengthening of the industrial structure through multidisciplinary collaboration between the academic sector, research institutes and companies. Likewise, they stand out in the design of personalized treatments in neurological diseases, proposing four main areas that define the scope of the project: Creation of brain maps on multiple scales, development of neurotechnologies for brain mapping, building, and promoting the industrial sector by commercializing cutting-edge neuroscience tools, and technology clusters25. A shared limitation in the study of the human brain is related to the willingness to donate postmortem brains, either for cultural, ethical, or ideological reasons in several Asian countries. They strive to achieve collaborations with brain banks in an attempt to reduce this limitation and promote campaigns to increase donations. Despite the fact that it is a project in development and with multiple challenges ahead, they seek to build a multiscale atlas of the human brain with the help of neuroimaging equipment, not only to advance in personalized medicine but also to study the relationships between the brain and mental illnesses, reducing cultural stigma and discrimination, reflected, for example, in the high suicide rates in the country25.

In Australia, the Australian Brain Alliance (ABA) consortium, created in 2016 and composed of 30 institutions, held the purpose of advancing the knowledge of the brain and the generation of results that can be transferred to the benefit of Australian society, the health, and the economy. In the same year they formalized the Australian Brain Initiative (ABI) project describing four challenges that shape its vision today: Optimize and restore the healthy functioning of the brain, develop neural interfaces for the recording and control of brain activity to restore its functioning, understand the neuronal bases of learning during individual development, and provide new computer knowledge inspired by the brain26. To advance in their ambitions they need to make a leap from basic research to practice; in this sense, they work on strengthening the relationships between university, industry and research centres, as wells as promoting the convergence of multidisciplinary scientific disciplines.

Progressively, the Australian commercial sector of neurotechnologies has gained greater positioning and international recognition, led by large innovative companies –Cochlear, Bionic Eye, Saluda Medical, EMOTIV, etc.27–, and counting, at the same time, with the support of ABI. Once again, the commercial strengthening of medical technologies along with the rise of AI in the country has raised ethical considerations about the increase in cognitive abilities and its civil and military application28, suggesting the creation of more solid action plans to reduce the potential hazards in the use and commercialization of neurotechnologies.

In Africa, several initiatives have been created around neuroscience and health; however, we will describe those focused on the study of the human brain. First of all, the African Brain Disorders Research Network (ABDRN)29, a network that brings together key participants from universities, companies, and funding agencies in order to facilitate the collection, treatment and sharing of brain data from the African population to promote research. Among other aspects, it is responsible for the promotion of the FAIR principles, the organization of educational activities to promote innovation. Secondly, the African Mental Health Research Initiative (AMARI) was created in 2015 and is currently in a second phase (until 2027) aimed at building networks of specialists and researchers in mental health, neurology and substance abuse, a consortium composed of six universities30.

There are six lines of research at AMARI, which include: Study of cognitive diseases related to HIV; Psychosocial interventions against maternal and child mental illnesses and the transmission of HIV; Psychosocial interventions in severe mental disorders, ranging from bipolar disorder to psychosis; Intervention against drug abuse; Mental illnesses associated with other physical or non-communicable diseases such as diabetes; and Support for caregivers. In this respect, the project adapts its research efforts to the most relevant social needs of its population, such as the development of intervention strategies against mental illnesses in mothers and children, progress in patients with HIV/AIDS and the organization of action plans in the face of emergency situations due to drug abuse.

Thirdly, The Brain Project (TBP), operational since 2017, is noteworthy, and lastly the Brain Research Africa Initiative (BRAIN), since 2018. The TBP31 differs from the rest of the projects in terms of its organisational structure, a non-profit organisation based in the US, composed of neurosurgeons, and related specialists, united to assist the African population free of charge, as well as offering training for health care providers in their region. Finally, the BRAIN project of Africa32 is an international organisation based in Switzerland and Cameroon, for the promotion of neurological health through research, education, and networking. They strive to gather empirical data for clinical decision support, dissemination of good practices in clinical neuroscience, training of new generations in neuroscientific fields, creation of innovative therapies for people with neurological diseases regardless of their financial situation, organisation of educational activities in mental health and the strengthening of collaboration networks.

Other noteworthy aspects from the neuroscientific initiatives in Africa, in addition to their collaborative networks, regarding diversification in lines of research, new trends and innovation, as is the case of neuroepidemiology33 to understand the distribution, frequency and risk factors related to stroke, multiple sclerosis, and transverse myelitis, as well as other trends including the study of other neuroimmunological diseases. In terms of innovation, the improvement of methods and therapies for neurological patients, for example, the development of quality-of-life questionnaires adapted to their population after suffering a stroke such as HRQOL34, as well as in diagnoses and treatments. Certainly, it is noticeable how they have directed their resources to a greater extent to innovation in healthcare practice and psychological intervention, relying on their strengths and, to a lesser extent, aimed at the development of neurocomputing technologies or digital atlas.

In Latin America, the Latin American Brain Initiative (LATBrain) project began in 2019 under a signed declaration between five countries in the region: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Cuba, and Uruguay35. They currently reach 10 countries, whose objectives are aimed at the development of new technologies, education, and knowledge transfer for the prevention and treatment of neurological diseases. Its strategic planning committee promotes the adherence of research institutes, laboratories, and non-profit associations36. In other words, their efforts are focused early on generating regional collaboration platforms that, among other aspects, facilitate the recognition of capacities and limitations between countries, the exchange of researchers that favour the knowledge spillover, the organisation of educational programs and workshops, together with the definition and differentiation with respect to the needs of each society in the mental and neurological field. In an effort to advance their objectives, each member country will coordinate local “Brain Initiatives” or reference centres36 to assist in identifying priority areas in the health and neuroscientific areas in line with LATBrain’s strategic plan. Among some of the topics explored in the symposiums organised were the COVID-19 and brain, neurodegenerative diseases and epilepsy, and disorders of pre- and early postnatal CNS development, among others.

Another more conservative initiative in terms of funding and structure is Black In Neuro, created in 2019 as a non-profit organisation in the US, whose mission lies in empowering the African-American community in neuroscience research and fighting racism37. Nevertheless, it is a project open to researchers with a passion for neuroscience and a desire to contribute to the academic and research field, regardless of their race or nationality. At the beginning of 2023, they reached 540 members from the US, Nigeria, and Canada, mainly. Black In Neuro is an active community in the organisation of seminars, discussion panels, mentoring programs, student exchanges, and recreational social activities that help them increase their networks and generate professional development opportunities.

Finally, in 2019 Europe formalizes the launch of European Brain ReseArch INfrastructureS (EBRAINS)4, the legacy of the emblematic HBP project, under the figure of an international non-profit association based in Belgium. In its beginnings, the infrastructure featured six independent services, each representing a set of technologies with different functionalities and capabilities around the brain, as a result of the interaction between the 12 interdisciplinary sub-projects38 that formed the HBP working groups and their co-design projects. Two years later, EBRAINS’ catalogue of digital technologies gathered more than 150 analysis programs, 90 models and 1,000 datasets of 1,110 international scientists39. The innovations are mainly aimed at data acquisition and processing (in compliance with FAIR principles), brain simulation and modelling at different scales, digital brain atlases that include genetic expression in different regions (human, monkey, rat, and mouse), computer medical platform with AI tools, neuro-robotics platform, and a virtual community or Collaboratory. As an innovation strategy, infrastructure services have been moving from stand-alone operation, integrating, and combining workflows, software, and data for better user experience in order to obtain a deeper, more advanced and dynamic analysis of the brain.

The figure 1 presents a chronological and synoptic overview of the main initiatives for the study of the human brain developed in the world during the 21st century.

FIGURE 1. Major global initiatives of the 21st century on the study of the human brain.

EBRAINS IN THE CONTEXT OF MENTAL AND NEUROLOGICAL DISORDERS

Before 2020, mental illnesses affected about 84 million people in the European Union alone, intensifying after the pandemic due to the COVID-19, according to a report published by the European Parliament40. The results of the survey conducted show that 46% of EU citizens have had psychological or emotional distress in the last year, such as depression or anxiety, and in Spain this percentage is higher: 54%. Young people between 16 and 24 years old are the most affected, women are more likely to develop mental disorders such as depression and anxiety compared to men, diseases prevail in older people with other neurological diseases, and socio-economic disparities between EU countries in the context of mental health are increasing.

Meanwhile, the latest report published by the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development)41 highlights the consequences of the pandemic and other influential factors, such as geographical, economical and risk. Although a slight post-pandemic recovery is manifested, some disorders such as depression maintain a high prevalence, influenced by external factors such as the high cost of living, climate crises and geopolitical conflicts. As for geographic factors, inequality is heightened between OECD countries, reflected in a higher risk of suicidal behaviour and, unlike the previous EU report, mortality rates are 3 times higher in men than in women. Economic factors encompass the development of public policies aimed at reducing the effect of these crises, some such as the inclusion of psychological emergency services. However, efforts are not enough to meet current needs, in which long waiting lists, high health costs, long distances to healthcare centres, difficult access to qualified specialists, marked regional differences, etc. prevail. Challenges also recognised in the Commission’s report.

In the spectrum of neurological diseases, the figures do not go unnoticed either. Annually, they are responsible for the deaths of 9 million people, being emphasized in low-income countries or with major shortages in their healthcare systems, according to a recent World Health Organization report42. In this sense, the most disabling neurological diseases until 2016, were strokes (42,2%), followed by migraine (16,3%), dementia (10,4%) meningitis (7,9%) and epilepsy (4,9%), mainly. In addition, 70% of people with neurological diseases live in low and middle-income countries43, whose healthcare systems lack sufficient human and physical resources to assist them. Likewise, one of the most recent studies on the burden of neurological diseases in Europe, analyses the incidence, prevalence, mortality, and disability in the region between 1990 and 201744. It is also noteworthy that, along with the United Kingdom, of the 512, 4 million people who lived in the 28 EU countries in 2017, more than 60% (307,9 MM) suffered from a neurological disease, and during that same year alone, about 74,5 million new diagnoses were recorded.

These global challenges have prompted the development of action plans that embrace society as a whole, from long-term programs promoted by public organisations and collaborative projects, to international and digital health initiatives. Likewise, health professionals and related researchers must equip themselves with technologies that can help them to manage these scenarios. Therefore, EBRAINS, although it is strongly linked to the context of neuroscientific research, in recent years has evolved towards a diversification of technologies to provide support to researchers in the clinical context. Examples of the first tools developed and are currently being incorporated into healthcare practice include: the VEP, TVB, the Medical Informatics Platform (MIP), Perturbational Complexity Index (PCI), the Virtual Research Environment (VRE) associated to Health Data Cloud (HDC), among others, which are discussed in the following section.

In parallel, different programs have emerged to support EBRAINS technologies in the context of mental and neurological health, under the figure of international consortia. Among them are: TEF-Health45; eBRAIN-Health46, integrated by TVB Cloud (TVB-Cloud) and AI-MIND; TVB Twin47; in addition to the six underlying supercomputing centres that are part of the FENIX consortium48: the Barcelona Supercomputing Center, the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre, Direction des Applications Militaires (CEA), the Jülich Supercomputing Centre, Consorzio Interuniversitario del Nord est Italiano Per il Calcolo Automatico and IT Center for Science.

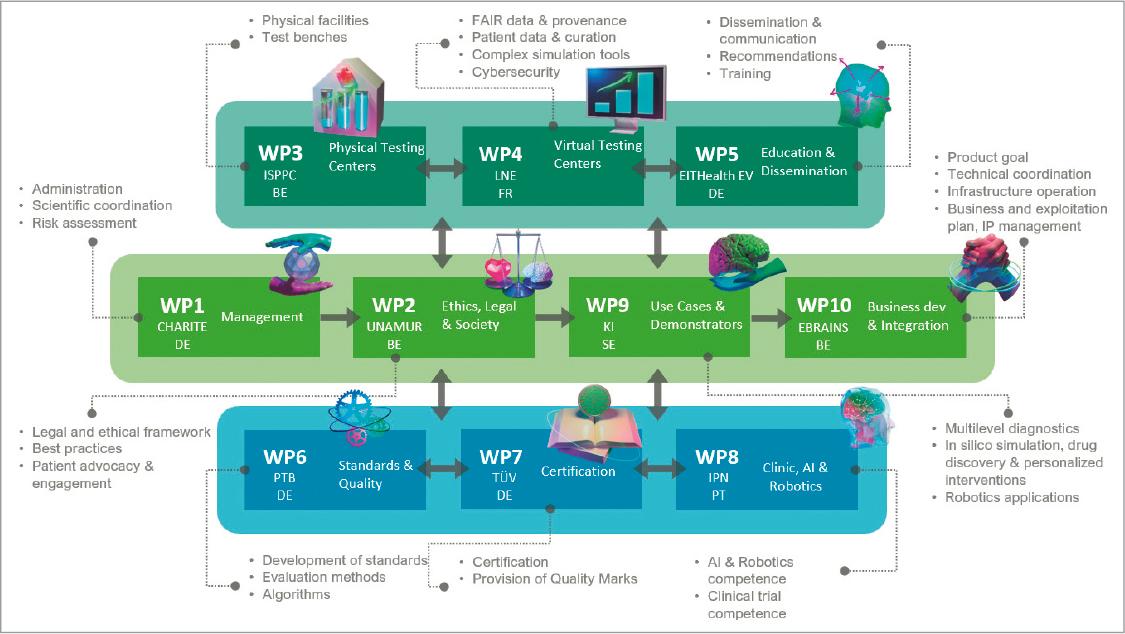

TEF-Health or Testing and Experimentation Facility for Health AI and Robotics45 is a consortium created in early 2023, mainly funded by the EU for experimentation, validation and certification of AI and robotics solutions in medical devices. It consists of 10 working groups with differentiated objectives (Fig. 2). They work on the creation of a network that combines physical and virtual environments to test the technologies developed within the framework of the EU’s Digital Europe Programme. In terms of its organizational structure, it has 51 members distributed across Europe, coordinated by the Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin. They seek to specialise in four areas: Neurotechnologies, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and intensive care.

FIGURE 2. Structure and working groups of TEF-Health (source: https://tefhealth.eu).

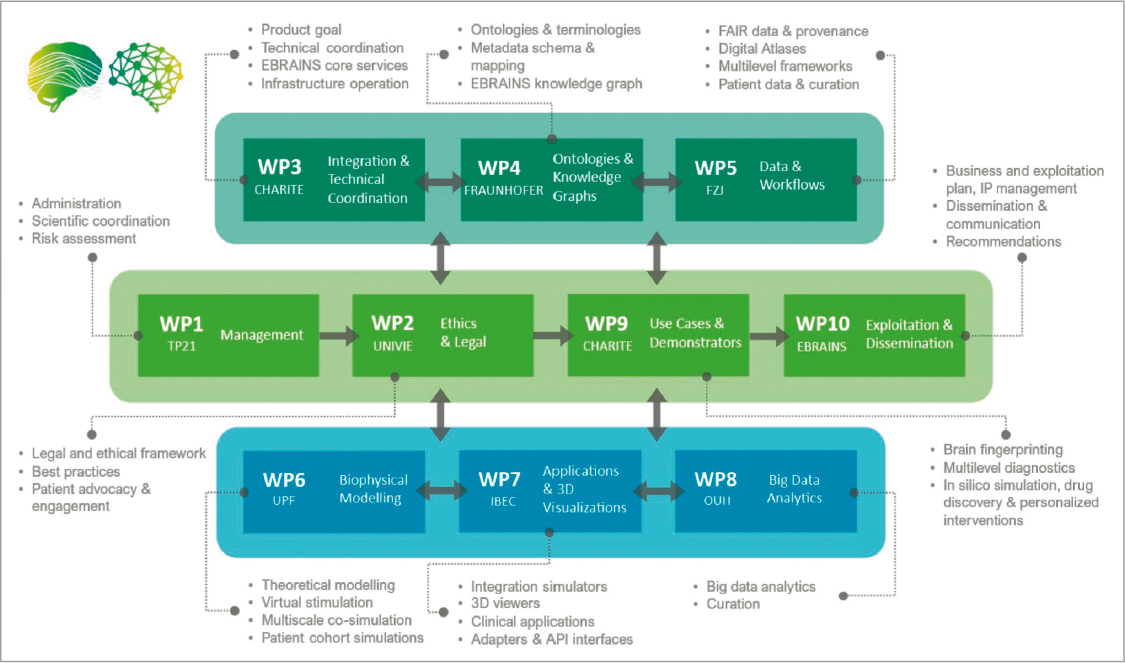

eBRAIN-Health is another large consortium promoted by EBRAINS co-financed by the EU in the field of neuroscience and health, composed of three projects in which 17 partners around Europe participate, and coordinated by Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin 46. It begins its activity in mid of 2022 with a 4-year time horizon, with the main objective of offering a platform for the creation of digital twins with data from patients and healthy people for the study of neurological diseases in a protected virtual environment (Fig. 3). The three programs that are of the project are: the HBP with the EBRAINS infrastructure; EOSC’s Virtual Brain Cloud and the trusted research environment for sensitive data; and H2020 AI-MIND with analysis tools for the study of neurodegenerative diseases and behaviour.

The innovation of TVB twins continues evolving inside and outside the EBRAINS infrastructure, specialising in a wide variety of neurological and psychiatric diseases, with customizable models for clinical use such as epilepsy, Alzheimer’s disease, ageing, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia and psychosis, among others49,50. In particular, early 2024, the launch of TVB Twin for Personalised Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders 47 oriented to schizophrenia, a disease that affects 5 million people in Europe alone and about 24 million people worldwide51,52. The project will culminate in 2027 and, among other aspects, neuroscientists are working on the development of multiscale brain models, along with the deployment of clinical trials in Marseille and Munich47, in an effort to support healthcare professionals in the quest for personalised treatments.

EBRAINS TOOLS OF INTEREST IN NEUROLOGY

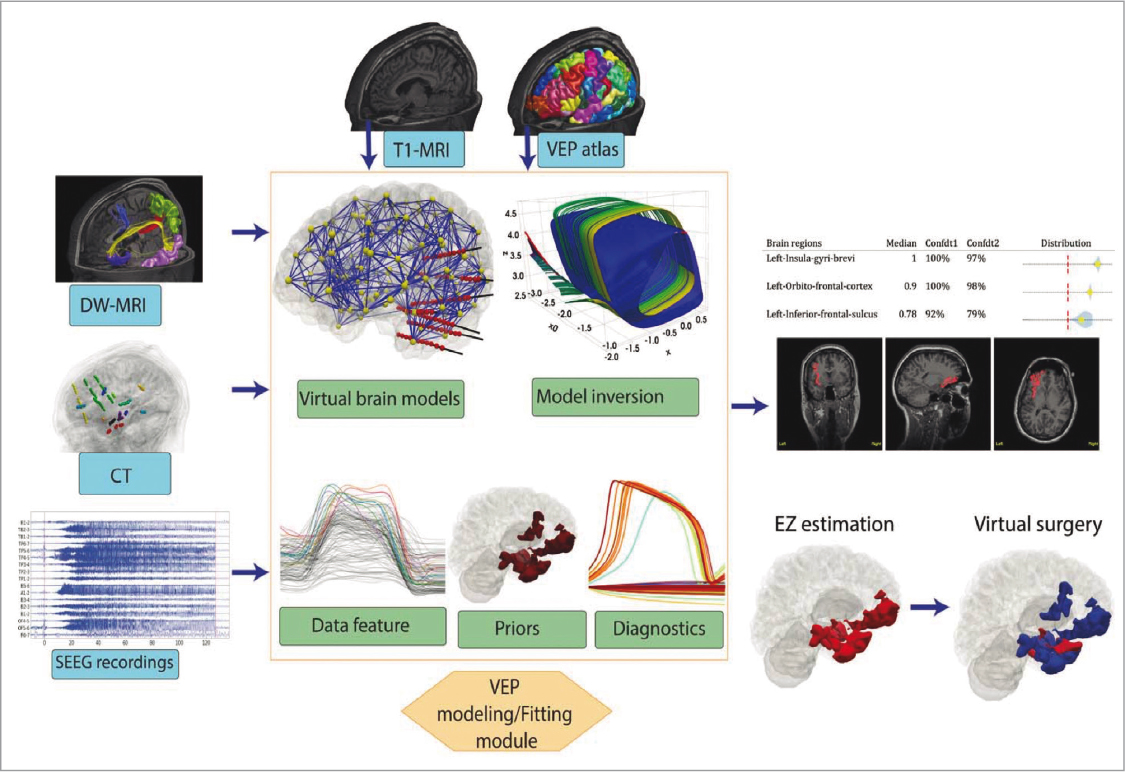

The VEP53 is a customizable multimodal probabilistic modelling system for patients with refractory epilepsy susceptible to surgical intervention. Fig. 4 offers a simplified scheme of the functioning of the VEP54, which analyses data from: structural and functional neuroimaging of each patient, stereoencephalography (SEEG), electroencephalography (EEG), video-EEG, magnetoencephalography (MEG) and neuropsychological evaluations, among others.

FIGURE 4. Operation of the Virtual Epileptic Patient (VEP) (source: Wang et al., 2022 54).

Subsequently, a model of neural networks created by the team called Epileptor is applied, composed of five variable states in three different time states, considering aspects such as ion concentration, energy consumption, tissue oxygenation and its characteristic oscillations of epileptic crises. The model helps to identify the epileptic zones and crisis propagations zones, necessary to determine more accurately the regions that could –or not– require surgical intervention. The technology is in an advanced phase of its current multicentre clinical trial in France: Improving EPilepsy Surgery Management and progNOsis Using VEP Software EPINOV55. It is maintained as an open-source tool accessible from the official website EBRAINS4 and TVB workflow49 thevirtualbrain.org, explained below.

TVB49,56 is a neuroinformatics platform for personalised modelling and simulation of neural networks of the whole human brain, based on biological connectivity obtained by neuroimaging (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], functional magnetic resonance imaging [fMRI], MEG) and EEG, SEEG, among other techniques. Likewise, this open-source technology allows data analysis using neural mass models and other analytical tools available in the software’s virtual catalogue, including visualisation of the generated models (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5. The Virtual Brain (TVB) (source: https://thevirtualbrain.org).

The TVB has evolved to be part of the cloud services of EBRAINS or TVB cloud software that includes, among other elements57: TVB software, connectome analysis or TVB Image Processing Pipeline, simulation on different spatial scales such as Multiscale Co-Simulation, automatic code generation with TVB-HPC, Bayesian VEP BVEP (part of the VEP), mouse brain simulation models or TVB Mouse Brains, datasets and metadata from cohorts of diseased patients and healthy subjects, associated brain atlas and modules to learn how to use the software with manuals and tutorials videos. Among other aspects of innovation and development, the TVB has contributed to the study of neurological diseases through its clinical application49,57; in addition to the refractory epilepsy mentioned above, stroke in adult and children, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, surgical planning for tumour resection, schizophrenia and psychotic illnesses, mild brain trauma, hypoxia, and autism.

The interoperability of the TVB includes the consortium HDC58 a federated platform of EBRAINS for storage, analysis and sharing of sensitive data, coming from a GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) accredited environment, the so-called VRE of Charité Universitätsmedizin in Berlin59, with partners in Switzerland, Sweden, Spain, Norway, and Greece (Fig. 6). To use the HDC services, some agreements must be signed in advance –General Conditions of Use, Non-disclosure agreement or Confidentiality Agreements–, in addition to obtaining the necessary approvals from the research centres involved and the corresponding committees.

FIGURE 6. Health Data Cloud (HDC) of EBRAINS (source: https://brainsimulation.org).

Afterwards, the Principal Investigator or Project Administrator is assigned a virtual space in HDC, who has the authorization to use the tools of the platform and invite other members of his team60. The advantages and innovations of HDC61 are diverse: as an alternative for the storage and sharing of sensitive data in Europe, control in the organisation of datasets, validation of data following FAIR principles and standardization methods, without format restrictions, among others. These are aspects that, ultimately, would help to reduce the reproducibility crisis in scientific studies, promote collaboration with other research groups in the field of neurological diseases and encourage the use of energy-efficient supercomputing networks.

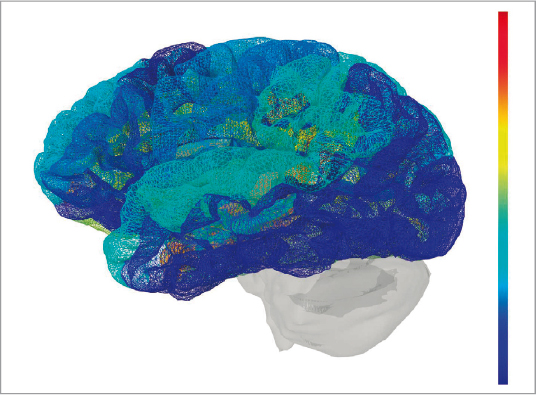

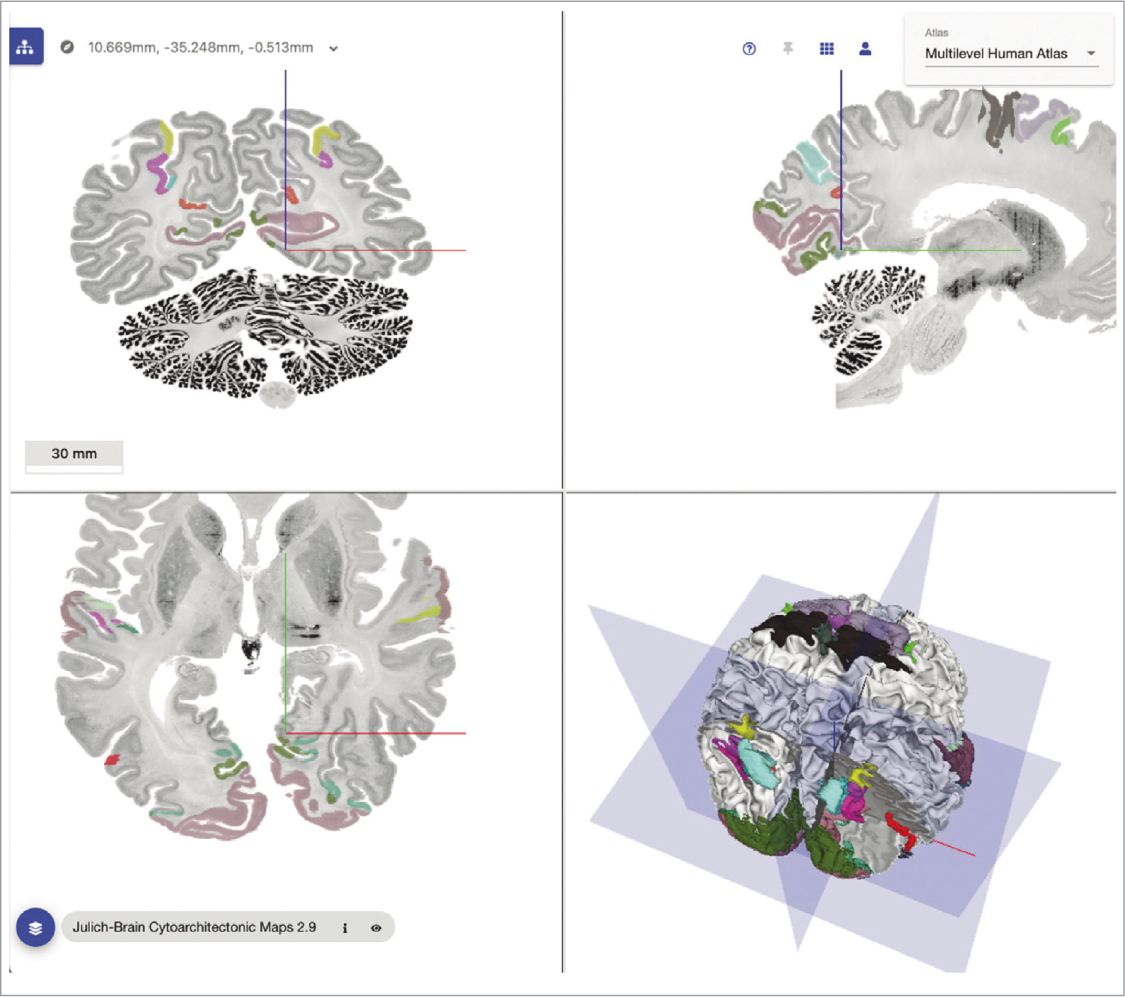

The Multilevel Human Brain Atlas62 technology of EBRAINS consists in the integration of different three-dimensional probabilistic maps of cortical areas and nuclei, inspired in the Julich-Brain Atlas. Among other aspects, multimodal data can be explored at the microscopic and macroscopic scale of the human brain, the cytoarchitecture, as well as studying the relationships between functional and structural connectivity (Fig. 7). From a microscale resolution, the atlas is based on the model created BigBrain, similar to a template that facilitates the virtual reconstruction of the cellular connectome of 10 postmortem brains, used as a reference of healthy people62 at a spatial resolution of 20 microns (µm).

FIGURE 7. Multilevel Human Brain Atlas (source: Zachlod et al., 2023 62).

The BigBrain system reflects in extraordinary detail the structure of the hippocampus, the cortical, subcortical and nuclei areas, etc.; while the macroscale perspective62 is based on reference systems or templates provided by the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) –such as the MNI Colin 27 o ICBM 152–, favouring connectivity between scales. The technology can be accessed through the Siibra software suite, a set of programs and datasets that connect with EBRAINS applications, facilitating the virtual exploration of different integrated maps, selecting areas of interest and associated metadata, accessing cohort data, performing analyses on genetic expression with JuGEx, and establishing correlations between fMRI and PET datasets.

Certainly, the Multilevel Human Brain Atlas reveals great usefulness in neurological and psychiatric fields. As a sample, a group of researchers from Jülich Research Centre (FZJ), Aix-Marseille Université (AMU) and the Heinrich Heine University of Düsseldorf (UDUS) build up an MRI database of 1,000 brains of people aged 55-85 years old63, allowing to reflect changes related to age and cognitive impairment through functional and structural data, both from the entire cohort at the individual level. Using the Atlas, the TVB simulator and data from EBRAINS’ Knowledge Graph, researchers succeeded in recreating virtual and personalised models of the brain, testing different hypotheses in the system based in the impairment of connectomes and their influence on cognitive functions. Once again, the combination of these technologies opens up a range of possibilities for inclusion, experimentation, and analysis of other variables, e.g. emotional, use of pharmaceuticals, diets, etc. Neurologists and other interested experts can request access to this database 1000BRAINS study 64 upon authorization from the authors.

In the EBRAINS universe, neuroscientific data management is a fundamental pillar that has enabled the generation and transformation of research ecosystems with innovations inspired by engineering and life sciences. Other examples include the MIP65,66, Human Intracerebral EEG Platform (HIP)67 and hundreds of highly useful datasets that have given rise to technologies such as The Digital Brain Tumour Atlas 68, The Human Connectome Project Young Adult fMRI time series69 or The Swedish National Facility for Magnetoencephalography Parkinson’s Disease Dataset 70 (NatMEG-PD), to name a few.

The MIP is coordinated by CHUV Lausanne University Hospital (Fig. 8). It is based on a technology of processing and analysis of different medical data from dozens of hospitals and associated research centres, whose federated structure confers a high level of security by keeping patient data within hospitals under a decentralised scheme. The MIP has diversified into federations that stand out in four areas65,66: dementia (6,348 records), epilepsy (5,970 records), brain injury (10.500 records) and mental health (7,300 records). Other relevant federations have recently joined such as Neuro Cohort on neurodegenerative diseases (32,550 records) and stroke (110,413 records), product of collaboration with other hospitals around Europe.

FIGURE 8. The Medical Informatics Platform (source: EBRAINS, 2023).

In addition to the MIP, the CHUV research team coordinates the HIP –associated to EBRAINS services–, that combines cured intracerebral EEG (iEEG) data performed in patients with refractory epilepsy and DBS61. Therefore, there is a diversity of data related to HIP beyond the iEEG records, such as neuroimaging data to locate electrodes, clinical, demographic data, cognitive and behavioural tests. The project is still under development, with approximately 12 associated European centres (one of them in Spain, the Hospital del Mar), which together are currently able to contribute to the growth of the database.

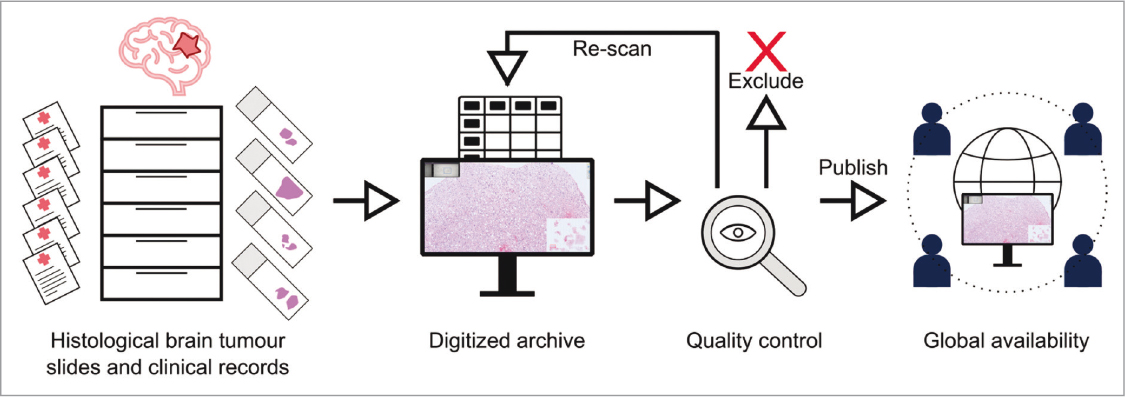

The Digital Brain Tumour Atlas 68 is a substantial source of histopathological data on brain tumours from the Division of Neuropathology and Neurochemistry of the Medical University of Vienna between 1995 and 2019. The collection of digitized samples not only includes tissue samples from a wide variety of tumours, but also from related and rare pathologies, clinical observations, surgical information, tumour location, etc. They have collected a total of 3,115 scanned samples from 2,880 patients and, according to the research team, they can be used for clinical (intertumoral comparison) and academic purposes (digital pathology based on machine learning algorithms), among others (Fig. 9).

FIGURE 9. Overview of the data acquisition and publication process of the Digital Brain Tumour Atlas (source: Roetzer-Pejrimovsky et al., 2022 68, and adapted from Meaghan Hendricks from the Noun Project).

Finally, The Human Connectome Project Young Adult fMRI time series 69 brings together functional and structural records from 785 participants. The project has provided the scientific community with information from resting-state fMRI, MEG, MRI, other physiological, genetic data, and cognitive tests. Likewise, datasets about Parkinson’s disease can be found in EBRAINS, such as those collected by the Swedish National Facility for MEG70, named NatMEG-PD. MEG and MRI records were made in 66 patients with the disease and 68 healthy controls available on the platform, which can be used to analyse changes in functional activity, study performance in cognitive activities and symptoms, among others.

EBRAINS NEUROTECHNOLOGIES IN THE CLINICAL CONTEXT: UPCOMING RELEASES

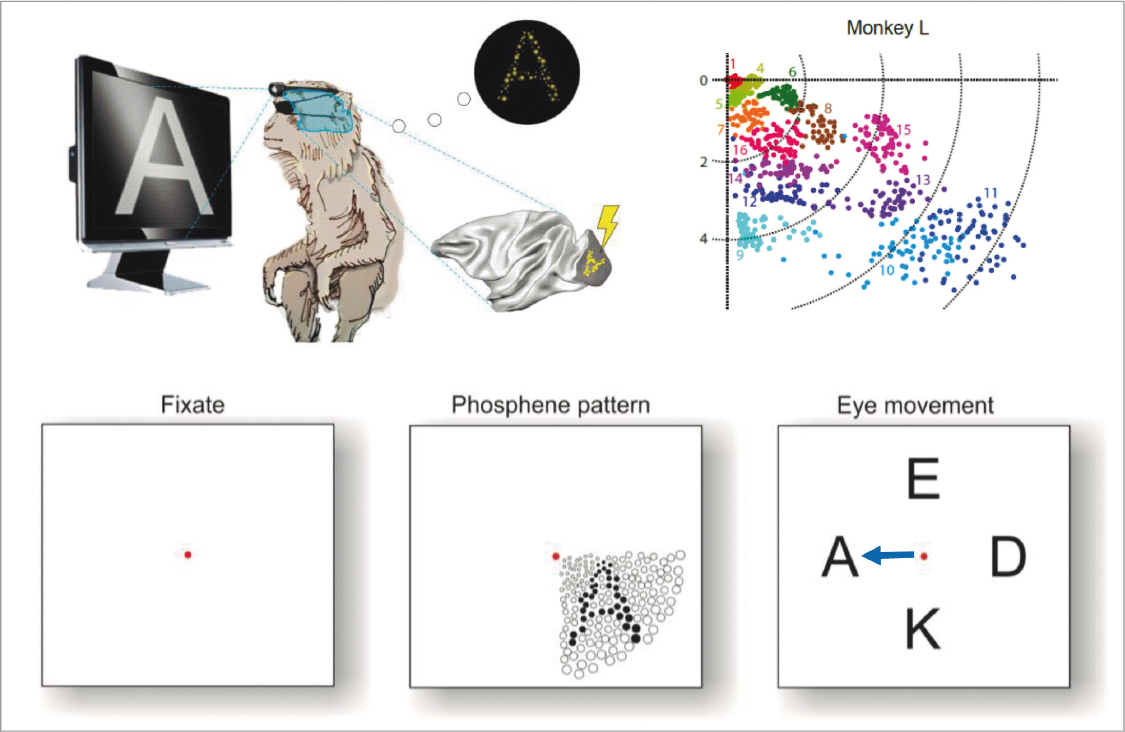

Some neurotechnological breakthroughs that began their development in the framework of HBP and EBRAINS, will possibly have a significant influence on sensitive neurological areas such as blindness or consciousness disorders. As for the first, a research team has designed a minimally invasive prosthesis with the aim of restoring vision, with a performance similar to DBS. The first results were published in the journal Science in 202071, from an experiment performed on two monkeys implanted with a system comprising 1,024 electrodes, stimulating the visual cortex, and generating phosphenes or flashes artificially (Fig. 10).

FIGURE 10. Recognition of the stimulus presented through the production of phosphenes in the visual cortex of the experimental monkey (source: Chen et al., 202071; Phosphoenix Team, 2023).

The authors highlight that simultaneous stimulation of electrodes in this study favour differentiation over shapes, while successive stimulation helps in the perception of movement. Another innovation that stands out is the number of electrodes they managed to integrate into the implant, having a substantial impact on the amplitude to generate phosphenes in specific areas of the visual cortex. In 2019, the spin-off associated with the Phosphenix project72 was created, they succeeded in raising venture capital in the pre-seed phase and are still actively looking for investors.

In relation to consciousness disorders, a group of researchers from the University of Milan developed a non-invasive method to measure their levels, called Perturbational Complexity Index (PCI)73, a technology created to assist patients who have suffered traumatic brain injury or brain damage. PCI is an index or measure obtained from the responses of a patient’s thalamocortical system to a perturbation or disruption using transcranial magnetic stimulation equipment with a high-density EEG, in which a statistical analysis is subsequently performed to detect the activation patterns caused by the induced disturbance (Fig. 11). Therefore, the method differentiates states of consciousness between wakefulness and sleep, levels of sedation, NREM sleep, vegetative states, etc. The technology has been validated in clinical environments with the collaboration of universities, hospitals, and associations worldwide.

FIGURE 11. Magnetic stimulation and EEG readings are used to measure a patient’s level of consciousness (image: Russ Juskalian).

As an example, recent studies that used PCI and AF (Fractional Anisotropy) in patients with severe brain injuries74, have empirically demonstrated how structural and anatomical integrity is highly related to the variability of effective connectivity (from the PCI) and, among other findings, both structural and effective connections are necessary for consciousness to emerge. Its developers have shared a module on the EBRAINS website, which allows to calculate the perturbational complexity and the steps needed to obtain the PCI, called Lempel Ziv PCI.

Other EBRAINS projects seeks to promote, organise, and contribute to technological development in the field of mental health from a common and collaborative framework, such as the Coordination and Support Action (CSA) BrainHealth75, and the European Health Data Space (EHDS)76,77. The CSA was created at the end of 2023 with the aim of creating a space for collaboration between European partners and other international communities specialising in mental health. It is coordinated by the German Aerospace Center (DLR) to identify new opportunities in the field of research and priority lines that will be part of the Strategic for Research and Innovation Agenda (SRIA), delimiting international actors, infrastructures, and developments. Whereas, in terms of security and data sharing, EHDS76,77 emerges as a health infrastructure created by the European Commission, incorporated into the Commission’s work programme in 2021 in the area of health digitisation, with the main objective of promoting the adequate exchange of health data for primary and secondary use. The pilot program is called HealthDara@Eu, comprising 17 members –including EBRAINS– with a 2-year duration, intended for secondary use of health data, e.g. for research, innovation, regulatory and other purposes.

Within the range of cerebrovascular diseases such as stroke, the Integrating AI in Stroke Neurorehabilitation78, project of EBRAINS coordinated by the Radboud Universiteit in Nijmegen, The Netherlands, is currently preparing a platform to develop and validate AI algorithms for their clinical applications. The associated services will include stroke data acquisition and access, analysis, brain simulation prediction, design, and improvement of empirically valid interventions. In the first phase of the project79, the efforts were directed to the data management plan, its organisation, legal and ethical aspects, etc. In the second and current phase, the configuration of the cloud infrastructure, data acquisition and processing, development of AI modules, rehabilitation protocols, as well as the pre-clinical trial organisation. In the third and last phase, the evaluation will be conducted, considering impact, security, user perspective, strategic and business plan.

Possibly, in the coming years, healthcare services will be strengthened with the use of AI-driven platforms with clinical validity and efficient safety protocols, oriented towards a comprehensive, agile, and more reliable diagnostic intervention. Comprehensive by being conceived as a patient-centred medicine that will, at the same time, provide support to caregivers and affected relatives; agile for contributing to timely diagnosis and rehabilitation therapies for stroke, from home or in the hospital; and greater reliability by considering prospective and retrospective longitudinal data. As reflected throughout the article, these advances will reach a wide range of neurological diseases. Examples such as the Virtual Multiple Sclerosis Patient 80, a customizable virtual model for patients diagnosed from multimodal data based on the individual connectome, or the Virtual Ageing Model, are today a reality.

CASE STUDIES ASSOCIATED TO THE SPANISH EBRAINS NODE

The Spanish node of EBRAINS81, coordinated by the Polytechnic University of Madrid (UPM), currently (as of late 2024) comprises thirteen organisations from both the public and private sectors: Bitbrain Technologies SL (Bitbrain), Fundació de Recerca Clínic Barcelona-Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (FRCB-IDIBAPS), Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Déu (IRSJD), Quirónsalud, Rey Juan Carlos University (URJC), Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia (IBEC), HM Hospitales’ Research Foundation, University of Granada (UGR), the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), IRB Barcelona, Carlos III Health Institute, and the Universitat Pompeu Fabra. In accordance with the available resources, expertise, and technological capabilities, its partners are committed to offer different services to the scientific community across the infrastructure.

Therefore, the technological offer varies from software tools (visualisation, modelling, and analysis of neural networks), hardware (advanced neurotechnology for brainwave recording, brain-machine interfaces), neuro-imaging equipment (MRI, MEG, optically-pumped magnetometer), electron microscopy, brain datasets at different scales and cohorts, among other state-of-the-art innovations. Moreover, two priority areas in biomedical research have been chosen as a starting point of the Spanish node: 1. Memory disorders and rehabilitation; 2. Neuromotor disorders and neurorehabilitation. Likewise, the leadership of the UPM has excelled in the field of innovation and technology foresight for HBP/EBRAINS tools82,83, as well as the creation of the interdisciplinary collaboration platform Neurotec (neurotec.upm.es)84, of interest for neuroscientists and neurotechnologists, both in Spain and internationally.

While each member of the Spanish node strives to provide valuable and useful contributions to the infrastructure, we will highlight representative case studies of the university-business-research triad: the MEG Facility of the CTB-UPM (Center for Biomedical Technology-UPM), given its contribution in scientific innovation and participation since HBP; the spin-off of the University of Zaragoza Bitbrain, for its trajectory and neurotechnologies in HBP; and IDIBAPS, for their scientific expertise as coordinators of the WP2 (Work Package 2) –Networks underlying brain cognition and consciousness– within HBP.

UPM

The UPM boasts a long track record in the neuroscientific and technological fields. Since its conception in 2008 it has evolved towards an interdisciplinary research approach, with the ambition to address the challenges in health and biomedicine85. Likewise, their infrastructure combines research laboratories with MEG services, neuroimaging, animal facility, and cell cultures, among others. Within the Spanish node, the UPM leads the MEG facility, the Optically-Pumped Magnetometer (OPM), the optical and electron microscopy, together with the Cajal Cortical Circuits Laboratory, mainly. The MEG equipment as a non-invasive technique86 has attracted enormous interest in the research and clinical field due to its high temporal and spatial resolution, compatible with other recording equipment simultaneously such as the EEG. In contrast, the OPM87 is a cutting-edge sensor technique that has emerged as an alternative to MEG equipment, i.e., it does not require cryogenic cooling, its flexibility allows its application in any part of the body, as well as the admission of movements by the subject during the test, without interfering with the sensitivity and resolution of the system.

Bitbrain

The neurotechnological spin-off of the University of Zaragoza, Bitbrain 88, began its trajectory in 2010 with a multidisciplinary team with experience in the brain-machine interface domain. Its products and services have diversified into the development of state-of-the-art neurotechnologies, research, health, and neuromarketing, ranging from recording devices (dry EEG, semi-dry EEG, neuroheadband EEG, biosignal recording, eye trackers), software (recording, metrics and AI analysis, visualisation, programming), comprehensive platforms (monitoring equipment, behavioural and cognitive recording, virtual healthcare), to consultancy and research services. In addition to Zaragoza, they are based in Barcelona and Boston, with allied distributors in Europe, Latin America, Asia, etc.

Bitbrain has been involved in several health-related projects, such as the HBP, AI4HealthyAging, BAYFLEX, Fluently, EBRAINS PREP, etc. In the framework of HBP, they coordinated the Neuro-Robin project, a closed-loop upper limb simulator89 inspired by the use of brain-machine interfaces for motor rehabilitation in stroke and spinal cord injury patients. This technology allowed, among other aspects, to combine HBP’s neurorobotics platforms, simulation tools such as TVB, and Bitbrain technologies in terms of software and hardware. Among the latest developments presented in EBRAINS, the EEG garment or based on smart textiles90 is noteworthy, a transformation of traditional recording equipment consisting of a system that does not require the use of wet electrodes and provides easy-of-use compared to similar technologies. The invention has allowed the exploration and inclusion of conductive textile materials integrated with sensors, bringing greater convenience to the user and lower production costs.

IDIBAPS

The Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS) is an operational centre since 1996 and accredited by the Carlos III Research Institute in 200991. As a partner of the Spanish Node, it provides the research community with a Neurological Tissue Bank, a repository holding more than 250,000 nerve tissue samples92 from various neurodegenerative diseases. In addition to the tissue bank, they also offer the use of a 3T MRI for humans and a 7T MRI for small animals and tissues for research purposes. Furthermore, they offer image acquisition (MRI, fMRI, DWI, spectroscopy, angiography) and processing services (volumetric analysis, voxel-based morphometry, functional and structural connectivity, texture analysis, etc.)93. Since the beginning of HBP, their research team has made several contributions in the field of brain activity, specifically in disorders of consciousness, sleep, and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease.

THE FUTURE OF DIGITAL TECHNOLOGIES IN NEUROLOGY

The future of neurotechnology and digital technologies in neurology promises profound and far-reaching transformations, enabling advances in diagnosis, treatment, monitoring, and follow-up, as well as in understanding the aetiopathogenesis and pathophysiology of diseases affecting the nervous system.

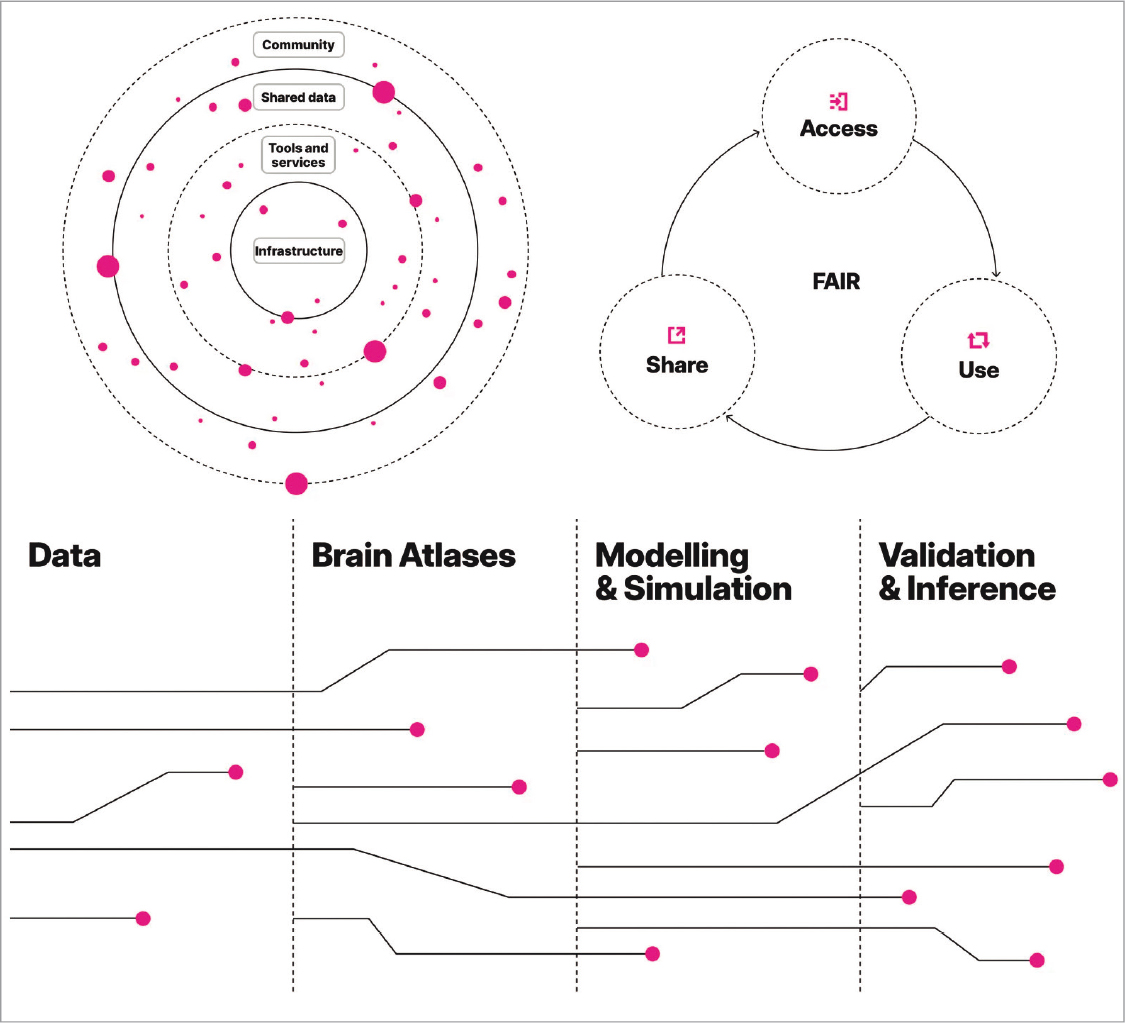

The myth of the 5P medicine (Personalised, Predictive, Preventive, Participatory, and Population-based), or 6P when Precision is included, is unlikely to be realised without collaborative work and the application of data science and engineering. In this context, clinical neurology and its related disciplines –paradigms of highly complex medical specialities– alongside cutting-edge initiatives such as EBRAINS and the array of technological tools at its disposal, some of which, though not all, have been discussed in this article, form an alliance that, if fully leveraged, will soon bear fruit. This is evidenced by some of the achievements being realised through the Spanish node of EBRAINS, as previously mentioned. The ultimate goal is to deepen our understanding of the nervous system, both in health and disease, to optimise diagnostic, preventive, and therapeutic methods, thereby benefiting society as a whole (Fig. 12).

FIGURE 12. EBRAINS: a state-of-the-art ecosystem for neuroscience. FAIR: Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability (adapted from: https://ebrains.eu).

The past 2 years have been prolific in advancements utilising cutting-edge neurotechnology to address severe neurological conditions. Several brain-machine interfaces have been published94, yielding remarkable results and achieving milestones that seem straight out of a science fiction novel95. These interfaces, whether invasive96,97,98,99 or semi-invasive100, are capable of interpreting brain signals –such as language or movement intention– and compensating for functions lost due to severe neurological deficits, such as those caused by stroke, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and spinal cord injury99. Such technological feats are only possible thanks to the collaborative efforts of interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary teams, the technology provided by initiatives like EBRAINS to the scientific community, and, of course, the exponential development of AI in all its forms.

If progress continues along this path, the near future will usher in a true 6P medicine, with neurology assuming a prominent role. Diagnoses will become increasingly early, precise, and specific (aetiological), reducing uncertainty and enabling preventive and therapeutic measures to be implemented in the initial stages of disease. Brain-machine interfaces will move beyond the laboratory and gradually make their way into clinical neurorehabilitation. New targets for deep brain and non-invasive stimulation will be identified. Patients will be continuously monitored through wearable sensors. AI will automate repetitive tasks in clinical practice and analyse large datasets (clinical, neuroimaging, EEG, genomic, and other omics data), enhancing predictive models while driving the development of cutting-edge neurotechnology in all its forms.

Finally, significant progress will be made in addressing the neuroethical, regulatory, and legal aspects of neurotechnology and AI applied to humans, safeguarding mental privacy, personal identity, free will, and other neurorights7,8,9,101,102. In this regard, all scientific societies related to the nervous system must act as their primary custodians, ensuring compliance and calling out violations.

CONCLUSION

The global race of initiatives focused on the human brain in the 21st century has brought Humanity one step closer to the noble ambition of deciphering, understanding, and predicting its functions.

While the most impactful projects in terms of associated multidisciplinary scientific groups, financial resources invested, and technological platforms developed have been the NIH BRAIN Initiative, the HBP, and the CBP, mainly, the universe of international programs continues to evolve, aspiring to strengthen its competitive advantages to find new answers to changing societal challenges. The initial project objectives, their most relevant limitations, some of the transformations they have experienced to give rise to the current results and those areas in which they are directing their efforts were identified.

The difficulties of these programs become increasingly complex for multiple reasons and, although beyond the scope of this article, those related to accessibility to funding and technological resources, cultural divergences, demand for successive redefinitions or adaptations on ethical principles and human rights around neurotechnologies, technological developments created in the context of neuroscientific research and with potential for long-term exploitation that face enormous difficulties in transferring them into healthcare practice or to meet the specific needs of diverse populations, risks on the dual use of emerging technologies, as well as greater pressure to crystallise in the shortest possible time research efforts along with a more efficient consumption of the resources obtained, are just the tip of the iceberg.

In parallel, in an effort to alleviate these limitations, a common factor among the initiatives has been the strengthening of collaborative networks, favoring the spillover of knowledge. In this sense, the needs in terms of specialised medical training on the most recent advances in neuroscientific and biomedical research are lessened, the existing training gaps between research teams in low- and middle-income countries and those in more advanced countries are narrowing, and the exchange of human talent is promoted, which, together with the use of digital platforms, stimulate the dissemination of technical knowledge at a breathtaking speed. In this global scenario, EBRAINS debuts as a digital infrastructure of reference in scientific research, whose associated projects continue to develop platforms, technologies and services oriented towards neurosciences, neurology, mental health and neurorobotics in a collaborative scheme.

In the field of neurology, the following platforms are available: TVB for simulation and modelling of neural networks of the whole brain; the VEP oriented to the simulation, modelling, and prediction of epileptic seizures, as a possible support tool in surgical planning for patients with refractory epilepsy; the HDC platform related to the VRE to store, analyse and share sensitive data with GDPR certification; the Multilevel Human Brain Atlas integrated by 3D probabilistic maps for the exploration of multimodal data; the MIP as a federated technology for the processing and analysis of medical data with AI algorithms; the HIP platform that combines cured iEEG data; and a variety of technologies of interest in brain tumours, as well as functional and structural neuroimaging recordings.

Focusing on Spain, the Spanish node of EBRAINS is currently (as of late 2024) composed of thirteen institutions from the academic, health, biomedical research, and business sectors; coordinated by the UPM. The interdisciplinarity and an incipient collaborative spirit confer the node an enriching innovation ecosystem oriented to neuroscience and neurotechnology. Two priority research areas have been selected, related to memory and neuromotor disorders, in which each participant offers technological resources, data or equipment in consonance with their strengths and capabilities. We highlighted three practical cases and innovations of the triad university, company, and research centre, given their trajectory from HBP and EBRAINS: Bitbrain, IDIBAPS, and the UPM.

Finally, the possibilities offered by these collaborative networks and the neurotechnologies emerging from EBRAINS for research and clinical neurology are immense. For clinical neurology to fully harness these frameworks and the technological tools they offer, practitioners must first become familiar with them. This has been the primary objective of this paper. Regarding the future that digital technology holds for neurology and related specialties, which has been briefly outlined here, it demands further projection, development, and profoundness, that will be the subject of a forthcoming work in this journal.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at DOI: 10.24875/KRANION.M25000091. These data are provided by the corresponding author and published online for the benefit of the reader. The contents of supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors.

FUNDING

This work has not received any official grant, scholarship, or support from research programs aimed at the preparation of its content.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to the content of this work.

ETHICAL RESPONSIBILITIES

Protection of humans and animals

The authors state that no experiments involving humans or animals were conducted for this work.

Data confidentiality

The authors confirm that no patient data are included in this work.

Right to privacy and informed consent

The authors confirm that no patient data are included in this work.

Use of generative AI

The authors declare that no generative AI was used in the preparation of this manuscript or in the creation of figures, graphs, tables, or their corresponding captions or legends.